haah.de

Vincent Tavenne

Exhibitions

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Interaktiver Käse

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

„V.T.“

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens bei Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

Nach woanders

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

An exhibition with works by Martin Gostner, Trixi Groiss, Hans-Jörg Mayer, Thomas Rentmeister, Ulrich Strothjohann, Vincent Tavenne, Iskender Yediler.

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Höhe x Breite x Tiefe

St. Gertrud, Cologne

Etroit, plat, mince (weit, tief, breit)

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

POLARISE-TOI

Saarlandmuseum Saarbrücken

Works by Thomas Arnolds, Tim Berresheim, André Butzer, Stephan Jung, Stefan Kern, Matthias Schaufler, Daniela Wolfer

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

With works by Jesko Fezer and Axel John Wieder, Thilo Heinzmann, Kai Helmstetter, Andreas Höhne, Stephan Jung, Stefan Kern, Martin Kippenberger, Martin Krützfeldt, Bruno Müller-Meyer, Markus Oehlen, Kiki Perleberg, Tobias Rehberger, Andreas Rüthi, Matthias Schaufler, Tatjana Steiner, Vincent Tavenne, Ina Weber, Georg Winter

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

L’UNIVERS TAVENNE

We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge. This would agree better with what is desired, namely, that it should be possible to have knowledge of objects a priori, determining something in regard to them prior to their being given.” (1)

In its spectacular diversity of forms, colours, materials and dimensions, Vincent Tavenne’s work not only opens up an abundance of contradictory sensory stimuli and spatial experiences. For it also directs the attention from a wide range of perspectives to the question frequently discussed in the history ofWestern ideas about the origin of the world in one’s own thinking, about the creation of reality by the human mind. To repeatedly encountered reflections on traditional cosmological conceptions, Tavenne contributes the view that the knowledge and comprehension of things is not only partly shaped by the cognizant subject, but additionally integrated in farreaching communication processes and determined by them. moi toi et ton moi, for instance, is one of the titles of a recently held exhibition, and Who are we, where are we going, how are you ? that of an earlier pioneering show of his works. In others of these in most cases onomatopoeic mottos with a deeper meaning that the artist chooses for his shows, such concepts as “univers”, “stratosphère”, “ether”, “beginning” and “black hole” arise. And in fact the very form of many works alludes to disc-like mediaeval depictions of the world, maps of the stars, globes and planetariums, while others drawing on the chambers of art and curiosities of learned Renaissance collectors display their own world of the miraculous. In purpose-crafted showcases, bizarre replicas of allegedly everyday finds are arrayed against a black background alongside microscopic arrangements of Tavenne’s stock of motifs —and finally termed Psycho Boxes. The viewer of the in most cases monumental gouache paintings may in turn be exhorted by an appeal expressed in the picture to conjure himself up (Cristallise-toi), atomize (Atomise-toi), concentrate (Concentre-toi) and even to polarize himself (Polarise-toi). The artist therefore makes use of elements of traditional cosmologies from a variety of origins and sooner or later undermines their lofty symbolism with irony—but without categorically rejecting the principles of their speculative models for interpreting the world and their search for the transcendental unity of the world.

Tavenne’s sculptural work is in large part characterized by a striking preference for elementary and universal forms and particularly for the circle and square. Back in his student days during the Eighties, the pupil of Norbert Kricke and later Ulrich Rückriem experimented with in many cases coloured disc, cylinder and cuboid elements of flexible materials like sheet metal or paper. A form’s translatability from two- to three-dimensionality (and vice versa) and the systematic interaction of image, body, colour and space preoccupied him just as much as the question of the role of the “content” of a pictorial work. His conclusion even in those days was to explicitly avoid committing himself. In other words, his sculptures and pictures exempt themselves on principle from the dictates of pre-coined meanings of objects and the hackneyed mechanisms of conventional image-object relationships. Instead, Tavenne seeks ways of engaging freely with the images of things and, by virtue of the distanced recapitulation of their artistically generated clichés shifted into the fictional, of creating new and unexpected ideas of them and of the web of things.

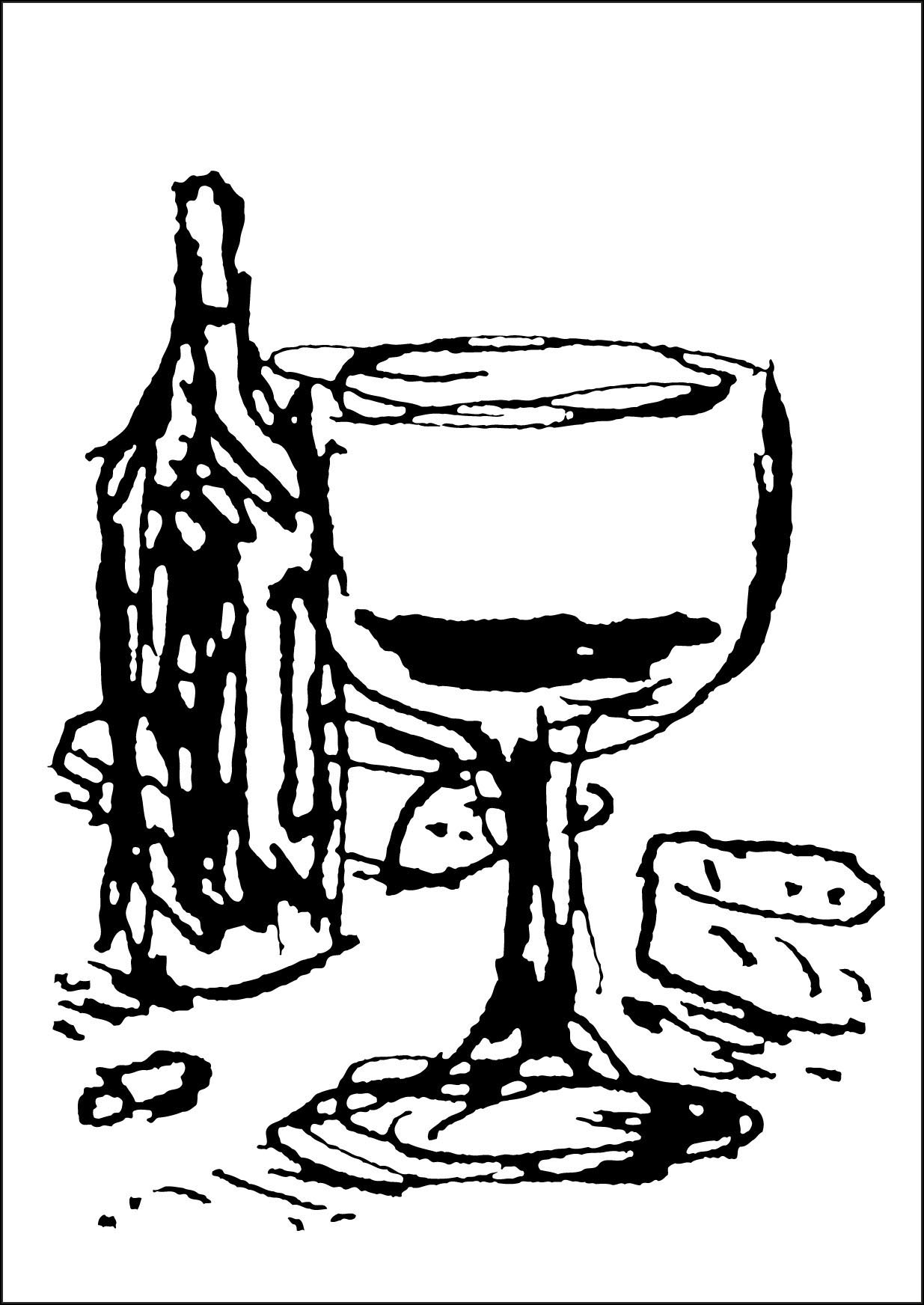

The choice of objects encompassed in this way stems, just as that of the materials and utensils for his work, in many cases from Tavenne’s thinking about his own identity, his origins, his family ties. A picture of his brother as a child, a bale of linen material from his grandmother’s dowry or a standard work of French cuisine — the investigation and processing of precisely such objects may lead one to suppose that for Tavenne, at least in art, the experiencer’s experience of himself, of his individually characteristic views and parameters of perception is also inevitably coupled with an experience of things. Such autobiographically inspired works often parody the stereotypes typically associated with them. By repeatedly modelling clumsy surrogates of such objects as wine bottles, hors d’œuvre dishes and Camembert boxes in plaster and ceramics over a period of years, Tavenne pokes fun, for example, at the nimbus of French food and drink culture also projected at his person. By increasing or reducing the scale of the represented delicacies, he makes recourse at the same time to the child’s-eye view and brings an air of magic into play. The originally “functional” character of the illustrated everyday objects is retained in essence by the work, but its conventionally assumed purpose is nonetheless exploded by the excursion into the fantastic. With such manoeuvres, Tavenne not only calls into question the perhaps thoughtlessly assumed interrelatedness of all things in everyday perception and action, but also undermines the aura of the work of art that inevitably accrues to any object, however banal, in the museum context.

A decisive ingredient of Tavenne’s working philosophy is mobility, the freedom from fixed studio rooms and elaborately worked materials. Unpremeditated technical realizability means to him — particularly in his early works—more than the desire to create something for eternity.He therefore usually prefers simple, lightweight and unassuming materials: Drawing paper, gouache colours, cardboard and sheet metal and, later, textiles and wood.

In his works executed in around 1990, he nonetheless examined the correlation of colour, image and space on a literally large scale. His room-filling installation Vinsang of 1991 at the Paris Weikhard-Cassaignau gallery seems to be carried by an almost demonstrative momentum. For this work, Tavenne coated one side of six large-format lengths of paper with high-gloss paint in various shades of red and freely suspended them, in pairs facing each other, from the ceiling to the floor of the room. These three colour-lined corridors were installed at right-angles to the usual traffic flow in the narrow gallery room, thus leaving only a roughly door-wide passage between the edges of the paper strips and the perimeter walls. The cramped and compact nature of the room situation achieved in this way forced the visitor firstly to move carefully and deliberately through the overall installation and secondly encouraged a very direct, close-range experience of the monumental red surfaces. Standing between these mixtures of picture and wall, the viewer found himself enclosed not only by the suddenly ungraspable breadth of a brightly coloured image space, but also by the changing blood-red reflected forms of his own body shimmering in the glossy coloured material. There may also be something exhilarating and dizzying in the force and vigour with which Tavenne here fuses colour and space. Vinsang, the onomatopoeic French paraphrase of his own first name, quotes the most dramatic connotations of the colour red (vin = wine, sang = blood).

The viewer’s comprehension of his own encounter with things is both visual and in this case, by virtue of the reflection, directly readable in the work’s appearance. From this, the role Tavenne expects the audience of his works to play is obvious, for he invites the viewer to attend an event conceived for him and possibly even to influence the event by taking an active part in the sculptural situation. It is no coincidence that numerous of his works allude to the world of theatre or the circus and arouse in the viewer-spectator the expectation of a spectacle, in whatever way it is conceived. With the accentuation of a sequential experience of the work, as already encountered in Vinsang, the artist also stresses that the space of the sculpture must always also be considered in a lively relationship with the viewer’s spatial system of reference.

With further unorthodox approaches to picture production, Tavenne participated in the debate in progress at that time on the identity and function of the picture. In his work Untitled of 1991, he pursues the aim of creating a highly monumental painting whose structure can be derived from the composition of an everyday object but which, by virtue of its method of creation, denies a pictorial representation. This experiment was based on the inherited, extremely voluminous cookbook, a thing therefore to which the artist has a special personal relationship. Its table of contents is represented here, dish by dish, by individual, coloured sheets of drawing paper. Each colour is chosen from the colour or taste freely associated by the artist with the food concerned. In a sequence following the listing in the book, the sheets are finally combined in gigantic collages — an additive, systematic construction principle in which arbitrary compositional criteria appear to be highly aptly excluded.

This work marked the beginning of a series of increasingly elaborate wall-filling paper works that Tavenne developed in the ensuing years from small-format drawings and photographs. The models — in many cases private snapshots in the spirit of the romanticized landscape — are transferred with the aid of a grid in most cases onto 64 sheets of A4. The sheets are then painted independently of each other with gouache and only stuck together afterwards. The inevitably mismatched edges of the freehand segments are accompanied along the bonded seams by a grid of continuous valley and mountain folds resulting from Tavenne’s approach of folding the assembled pictures together and opening them up again like a map. As a consequence of the effort taken to create distance, the banality and estrangement of the supposedly lofty and significant objects depicted become even more palpable. Because of the disproportionality of scale and the forced meagreness of their aura, the presented landscapes may even conjure up the scenario of photographic wallpaper in stuffy rooms. With its poor-imitation quotes from the clichéd beauty of nature, Tavenne presents the eye with an exemplary case of degenerate image-object relationships — almost as if to demonstrate how far the image of an object can be taken towards unpredictability and lead the viewer astray. In this process, the dismantling of these clichés is effected with a system of conceptual operations.

From 1994 onwards, concurrently with such “landscape pictures”, he fabricated his first monumental textile objects, today considered by many to be central to Tavenne’s sculptural output and usually also an active feature of his strongly relational exhibitions.

For Tavenne’s border crossings between two- and three-dimensionality, movable textile fabrics seem to be the genuinely predestined material. Fabrics can be highly effective both with a two-dimensional spatial extension and by defining a three-dimensional volume. Although the days when textile art was held in high esteem in its own right lie centuries back, Tavenne nevertheless refers to this tradition with his inventive colouration and his patchwork assembly of textile materials. It is precisely in this group of works that we find particularly direct linkages with his own biography, because the fabrics that the artist processes are not usually purchased from the factory and hence neutral, but functional textile objects with their very own story.

Tavenne’s interest in textiles as a material was only aroused when, during a stay in his home town, he was given the opportunity to artistically process a bale of ancient linen that had long been in the family’s possession. He decided to make a kind of housing out of this material and recalled a small paper sculpture created almost ten years earlier, a model of a pavilion-like building with eight slender columns and dome segments. He now applied this figure to an as it were “life-size” textile spatial corpus. The delightful paradox of a pavilion is that it is architecture without any use in its own right and the function of the round structure open on all sides lies primarily in its ornamental effect on its surroundings. At the same time, the archetype of a pavilion realized here makes use of a universal architectural vocabulary, e.g. the highly symbolic basic forms of the circle and octagon or the idea of a central space. However, this “construction”, whose elementary characteristics ought otherwise to be predictability and static functionality, literally has the bottom knocked out of it with Tavenne’s linen replica. The flimsy cloth envelope, sagging and bulging, only retains its shape by virtue of a system of strings and wooden strips from which it is suspended like a puppet — as the ghost of a building whose ephemeral appearance at any rate is no longer dictated by its contact with the ground. In the following year, Tavenne took the next step towards self-supporting and in most cases walkable “tent sculptures”. In our imagination, tents are associated with the most primitive and earliest form of architecture, having been part of human history for tens of thousands of years. These archaic dwellings generally adopt simple geometric forms based on the circle or rectangle, which ties in with Tavenne’s longstanding interest in three-dimensional elementary forms. Passed on from one generation to the next, the tent as a category has neither beginning nor end (like all nomadic architecture) and, as a result of its repeated re-use, is subject to the ongoing modification of its form in the course of time. The textile building gives rise to notions of departure and return and dreams of unlimited mobility and development in space.

And with the tent objects, the viewer’s behaviour and feelings in the room also become a much discussed theme of Tavenne. In the interior of his cloth sculptures, he creates a setting largely liberated from the usual points of reference or signposting systems of the “outside” world. The experience of these spaces is all the more extraordinary in that the character of the outer membrane of the sculpture often contrasts sharply with that of its interior. Tents of clown-like patchwork material or circus tents are converted inside into deep-black, lightless meditation rooms, and a spacious circular structure ultimately consists solely of claustrophobically narrow spiral passages.

Tavenne has a preference for establishing relationships between several such monumental textile objects at once, grouping them together and creating formal and thematic affinities between the spheres, cubes and cylinders. Viewed together, with their spatial bodies superimposed on each other, the viewer becomes conscious of their visual quality, a quality that the artist underscores with the colouration and mode of attachment of their outer envelopes.

For the ground plan of his tents and, as of 1998, for the corpus of his sculpture as well, he concentrates on the universal form of the circle. As a figure of supreme symmetry, the circle is also, as it were, without beginning or end, a familiar symbol of perfection and eternity since time immemorial. Several of Tavenne’s spherical sculptures allude to these connotations of the circle frequently taken up in Western architectural history. The symbolic significance of measure and number for the relationship between man and the cosmos expressed in the cosmologies of the Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages seems to be of genuinely far-reaching importance for these works.

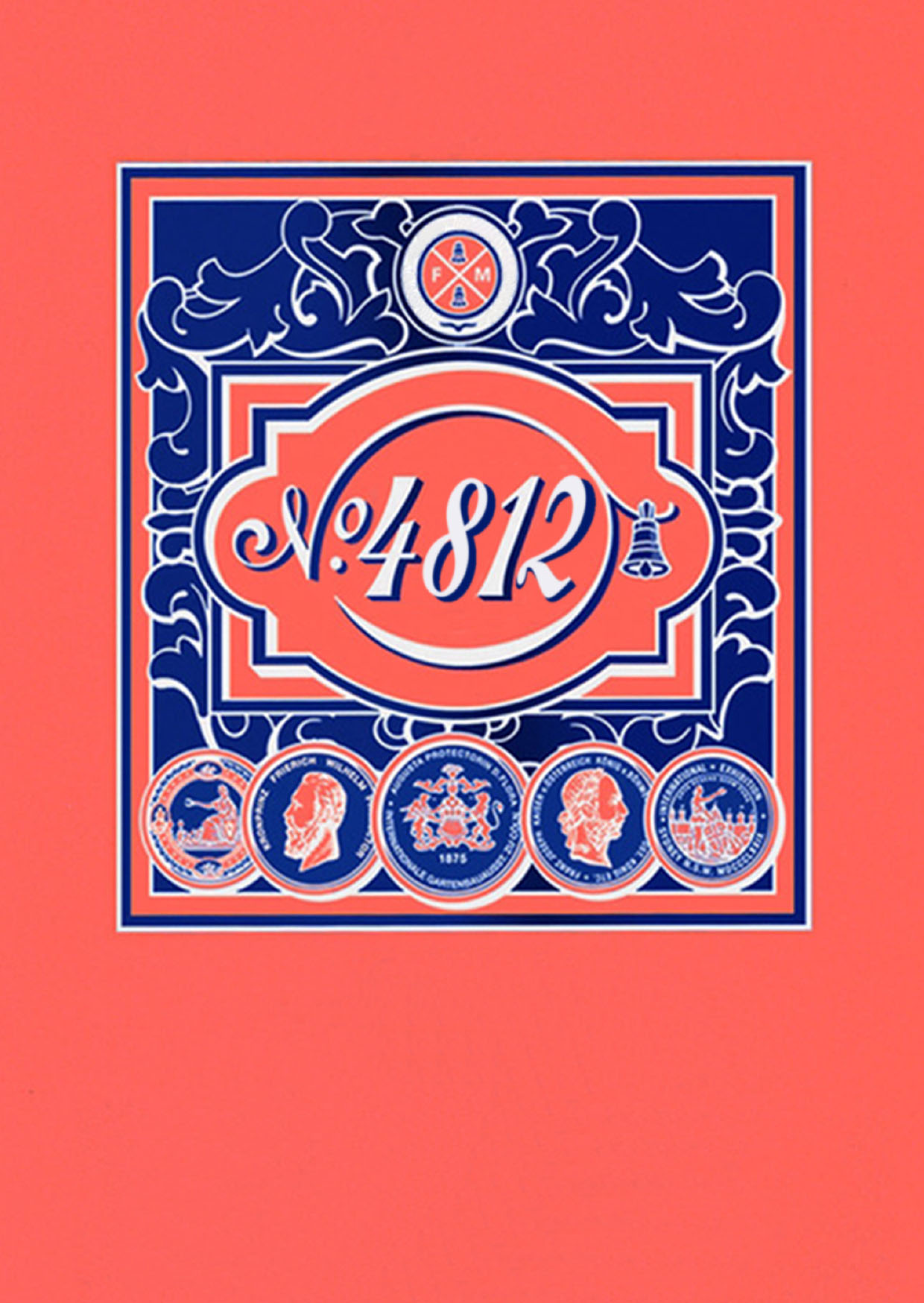

Even leaving aside his textile objects, the circle and its function in the code of historical representations of the cosmos is a recurrent source of inspiration for the artist. The nucleus of a complex group of works that evolved comover a period of many years can be found in a manuscript dating from the beginning of the 13th century, a preciously illuminated Bible (2). Here, illustrated in a prominent position, the figure of God, the creator and, in accordance with the understanding of the time, “master builder of the world”, spans the earth’s disc with a gigantic pair of compasses. This idea of invention as a process of drafting derived from Antiquity, the pointedly rational, even intellectualized process of creating the world, undoubtedly has a special appeal for Tavenne. The cosmos, a circular element with an organically undulating, leaf-green border and proliferating dark internal forms, symbolically fashioned by the God Father, is paraphrased by the artist in a gouache drawing of 2001, which can be regarded the first in an extensive series of pictorial and sculptural works. All formal development is now based in utterly radical consistency on the symbol-laden figure of the circle. Its countless graphic variants, across whose underlying surface radial, wave-like or spiral configurations unfold, indicate the power of cosmic forces in a seemingly premeditatedly restrained manner; in most cases, a precisely contoured coloured border fixes the overall spherical shape. In several pictures, a polyp-like interior figure identifies the curved outline as a cell membrane, in the centre of which unpredictable organic processes take place and ghostly emblems light up. On other sheets, circular forms merge to yield fantastic planetary constellations or evoke black holes of unfathomable depth.

The monumental sculptures of this group of works, also inspired by the figure of the mediaeval flat earth, demonstratively display a production process which is highly elaborate both conceptually and technically. In connection with the underlying circle form, its members are combined in a methodically in each case different structural configuration. The highly individual proportions of the various compartments are derived from, for instance, radial systems or spiral or square forms that contrast and conflict with the fundamental shape of the circular contour. No less remarkable than their structural organization is the overwhelming size of these rings and discs. The viewer is now suddenly confronted by a green “earth border” of the biblical creation of the world almost twice his own size, leaning loosely as a graspable object against the wall of the room. In the same position, the mighty facetted wooden ring is reminiscent of a gigantic frame or a heavy portal. The closed, glossy black disc, finally, with its interlocking internal structuring reflects the exhibition roomand the approaching viewer while also being open to interpretation as a both enticing and dizzying black hole. Tavenne’s disc constructions, which as sculptures once again explore the relations between the flat formand the volume, can also be regarded as a frame-like sight trained on those ideas and subjects depicted in the reflected cosmological models.

In 2005, Tavenne established a new genre within his œuvre, that of the Psycho Box mentioned at the beginning. These are assemblages of eccentric revenants of banal everyday objects and curious artefacts arranged by the artist in wall-mounted glass cabinets lined in black. In view of these undecodable, strangely clumsy scenarios whose nevertheless encyclopaedic aspirations remain clearly apparent, the viewer seems to be once again to be guided to a fundamental issue: for him, just as for everyone else, the perception of appearance and reality depends on the visual and bodily experience of the world. All knowledge and revelation through observation is based on the perception of the world from the subject’s vantage-point. The objects glowing in the darkness between the reflections of his own body become visible or remain concealed, depending on the degree of superimposition or penetration with the reflected self. There is no more apt way of demonstrating that the image of things and the creation of their reality depend on the attitude that the viewer adopts towards them, just as towards his own ego.

(1) Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason [1st edition, 1781(A), 1787 (B)] [translated by Norman Kemp Smith], published by Wilhelm Weischedel, Darmstadt 1983, p. 25.

(2) Bible moralisée, 1220/30, height 34.4 cm, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 2554, fol. 1v (The Creator).

L’UNIVERS TAVENNE

Que l’on essaie donc enfin de voir si nous ne serons pas plus heureux dans les problèmes de la métaphysique en supposant que les objets doivent se régler sur notre connaissance, ce qui s’accorde déjà mieux avec la possibilité désirée d’une connaissance a priori de ces objets qui établisse quelque chose à leur égard avant qu’ils nous soient donnés (1) »

Dans sa spectaculaire diversité de formes, couleurs, matériaux et dimensions, l’œuvre de Vincent Tavenne offre une foule d’excitations sensorielles et d’expériences spatiales contradictoires. À partir des perspectives les plus variées, elle attire également l’attention sur la question de l’origine du monde dans notre propre pensée et la création de la réalité par l’esprit humain, fréquemment discutée dans l’histoire des idées occidentale. Chez Tavenne, la réflexion récurrente sur les concepts cosmologiques traditionnels se combine avec l’idée que la connaissance et la compréhension des choses sont non seulement coproduites par le sujet connaissant, mais aussi déterminées et intégrées dans des processus de communication extrêmement vastes. C’est ainsi qu’une installation récente s’intitulait Moi toi et ton moi, tandis qu’une exposition pionnière plus ancienne portait le titre Wer sind wir, wohin gehen wir, wie geht’s dir?, c’est-à-dire « Qui sommes-nous, où allons-nous, comment vas-tu ?». Parmi ces épigraphes souvent homophoniques et à double sens dont l’artiste accompagne ses œuvres, on découvre également des termes tels qu’«univers », «stratosphère », «éther », « commencement » ou « black hole ». Or, la forme de nombreux travaux fait effectivement allusion aux disques plats représentant la terre au Moyen Âge, à des cartes astronomiques, des globes et des planétariums. D’autres exhibent un univers merveilleux inspiré des cabinets d’art et de curiosités des collectionneurs érudits de la Renaissance : se détachant sur le fond noir de vitrines menuisées à cet effet, de curieuses répliques de soi-disant trouvailles du quotidien s’assemblent en de microcosmiques arrangements du répertoire de motifs de Tavenne, qui les appellera finalement Psychokisten, ou « psycho-boîtes ». Quant à celui qui regardera ses gouaches souvent monumentales, un message formulé dans le tableau l’invite à s’invoquer lui-même (Cristallise-toi), à se pulvériser (Atomise-toi), ou au contraire à s’enrichir par la concentration (Concentre-toi), voire à se polariser (Polarise-toi). L’artiste fait donc intervenir un vaste éventail d’éléments participant des cosmologies traditionnelles, dont il va tôt ou tard saper ou tourner en dérision la noble symbolique – sans pour autant rejeter catégoriquement les fondements de ces schémas d’interprétation du monde spéculatifs et leur recherche de l’unité transcendantale du monde.

Les créations sculpturales de Tavenne sont, pour une bonne part, déterminées par sa prédilection pour les formes élémentaires et universelles, en particulier le cercle et le carré. Déjà pendant ses études dans les années 1980, l’élève de Norbert Kricke et ensuite d’Ulrich Rückriem expérimentait avec des formes discoïdales, cylindriques et parallélépipédiques souvent exécutées en couleur et dans des matériaux flexibles tels que la tôle ou le papier. La possibilité de faire passer une forme bidimensionnelle dans les trois dimensions (et vice versa), l’interaction systématique entre l’image, le corps, la couleur et l’espace l’intéressaient tout autant que la question du rôle du «contenu» d’une œuvre plastique ; à l’époque, il était parvenu à la conclusion qu’il faut explicitement éviter de définir ce contenu. Il allait donc adopter comme principe que ses sculptures et ses peintures doivent se soustraire au dictat des significations préétablies et des mécanismes rebattus présidant aux relations image-objet conventionnelles. Tavenne s’emploie à trouver des moyens pour jouer librement avec l’image des choses ; grâce à la reprise distancée de leurs clichés travaillés avec art, qui sont ainsi transposés dans la dimension du fictionnel, il tente de proposer des lectures inédites de ces objets et de la texture des choses en général.

Le choix des sujets qu’il aborde de cette manière, comme d’ailleurs celui des matériaux et des outils de travail, est souvent le fruit des réflexions sur sa propre identité, son origine et ses liens familiaux. Une photo d’enfance de son frère, un rouleau de lin provenant du trousseau de sa grand-mère ou un grand livre classique de la cuisine française – le fait de retravailler de tels objets laisse pressentir que pour Tavenne, une expérience des choses est forcément liée à l’expérience que le sujet fait de lui-même, avec ses points de vue et ses paramètres de perception personnels – et ce d’autant plus quand il s’agit d’art.

Souvent ses œuvres d’inspiration autobiographique parodient les stéréotypes qui y sont associés de longue date. Quand, au fil des années, Tavenne fabrique encore et encore de maladroits succédanés de bouteilles de vin, de plateaux de hors-d‘œuvre ou de boîtes de camembert modelés en plâtre ou en céramique, il se moque aussi du prestige de la cuisine et des vins français qui rejaillit sur sa personne. Par le biais de l’échelle généralement sur- ou sous-dimensionnée de ces alléchantes denrées, il fait en même temps référence aux horizons de l’expérience enfantine et introduit une dimension de contes de fées. L’essence du caractère initialement «fonctionnel » des objets quotidiens représentés reste préservée dans l’œuvre d’art, mais sa signification courante est détournée par une exagération versant dans le fantastique. Avec de telles manoeuvres, Tavenne remet en question les liens supposés unir (peut-être inconsidérément) toutes choses entre elles dans la perception et l’action quotidienne ; de plus, il s’attaque à l’aura de l’œuvre d’art qui vient immanquablement s’attacher à tout objet placé dans un contexte muséal, aussi banal soit-il.

Parmi les aspects déterminants de la méthode de travail de Tavenne, il y a la mobilité, la volonté de ne pas dépendre d’un atelier fixe et de matériaux qui exigent une mise en œuvre élaborée. La spontanéité de la réalisation technique est plus importante – surtout dans ses premiers travaux – que le souhait de créer une œuvre pérenne. En règle générale, il privilégie donc des matériaux simples, légers et sans prétention : papier à dessin, gouaches, carton et tôle, plus tard textile et bois.

C’est littéralement à grande échelle que la corrélation entre couleur, image et espace devient la thématique de ses travaux réalisés autour de 1990.Vinsang, une installation de 1991 qui occupait tout l’espace de la galerie parisienne Weikhard-Cassaignau, semblait animée d’un élan quasi ostentatoire. À cette occasion, Tavenne avait peint le recto de six rouleaux de papier grand format avec une peinture laquée étincelante dans différentes teintes de rouge, puis il les avait laissées pendre librement, par paires se faisant face, du plafond jusqu’au sol de la pièce. Ces trois corridors tapissés de couleur étaient installés perpendiculairement au sens de la marche dans l’espace très allongé de la galerie, si bien qu’il ne restait à chaque fois qu’un passage mesurant à peine la largeur d’une porte entre les bords des bandes de papier et les murs. L’étroitesse et la compacité de la situation spatiale ainsi obtenue obligeait le visiteur à faire attention et prendre conscience de ses mouvements au sein de l’installation, tout en favorisant un contact très direct et rapproché avec les monumentales surfaces de couleur rouge. Debout entre ces hybrides à moitié tableau/moitié mur, l’observateur se trouvait soudain enveloppé par l’immensité insaisissable d’un espace pictural rayonnant de couleur, mais aussi par les reflets fantomatiques fluctuants sur fond rouge sang de son propre corps renvoyé par la matière colorée scintillante. La force et la véhémence avec lesquelles Tavenne fait ici fusionner couleur et espace se teinte d’une certaine ivresse ou de vertige : dans la paraphrase homophonique de son propre prénom, Vinsang fait référence au vin et au sang tout en évoquant les connotations les plus dramatiques de la couleur rouge.

L’expérience visuelle de notre propre rencontre avec les choses – ici, directement perceptible dans la manifestation de l’œuvre grâce aux reflets – illustre bien le rôle que Tavenne entend attribuer au public de ses travaux : il lui propose d’assister à un événement conçu à son intention, voire d’influer sur cet événement en tant que participant actif à la situation sculpturale. Ce n’est pas un hasard si de nombreux travaux font allusion au monde du théâtre ou du cirque et plongent le regardeur-spectateur dans l’attente d’un spectacle, quelle qu’en soit la teneur. Avec l’accentuation d’une expérience séquentielle de l’œuvre, déjà présente dans Vinsang, l’artiste souligne également que l’espace de la sculpture doit toujours être envisagé dans une relation vivante avec le système de référence spatial de l’observateur.

C’est encore avec d’autres concepts peu orthodoxes sur la production de l’image que Tavenne a pris part aux débats sur l’identité et la fonction de l’image qui faisaient rage à l’époque. Dans son travail Sans titre de 1991, le projet consistait à créer une peinture monumentale dont la structure dérive effectivement de la configuration d’un objet appartenant à la vie de tous les jours, mais qui, en raison de son mode de réalisation, refuse de proposer une « signification » figurative. Cette expérience était basée sur le volumineux livre de cuisine évoqué plus haut, un objet avec lequel l’artiste a un lien personnel particulier. Ici, la table des matières est représentée – recette après recette – par des feuilles de papier peintes avec une couleur choisie en fonction des qualités que l’artiste associe à chaque plat selon sa couleur ou sa saveur. Suivant l’ordre de la classification du livre, ces feuilles sont ensuite assemblées en de gigantesques collages – un principe additif de construction systématique, dont sont manifestement exclus des critères de composition arbitraires.

Cette œuvre marque le début d’une série de travaux sur papier occupant toute la surface d’un mur, de conception de plus en plus élaborée, que Tavenne développe dans les années suivantes à partir de dessins et de photos de petit format. Les modèles – souvent des instantanés privés dans l’esprit de paysages romantiques – sont généralement reportés sur 64 feuilles A4 au moyen d’une grille quadrillée. Ces feuilles sont ensuite peintes à la gouache, chacune séparément, puis collées ensemble. À la jonction forcément imparfaite des segments de motifs tracés à main levée s’ajoute, le long des lisières du collage, une trame de pliures ou de cassures continues sur l’envers et l’endroit, qui résultent du fait que Tavenne plie et déplie ces grands collages suivant le principe d’une carte routière. Compte tenu de cette intervention artificielle, la banalité et le détournement des objets représentés, supposés nobles et chargés de significations, est d’autant plus sensible. Dans la démesure de l’échelle et la médiocrité voulue de leur apparence, ces paysages peuvent faire songer au scénario de certains papiers peints photographiques ornant des chambres étouffantes. Avec ces citations frisant le mauvais goût d’une beauté naturelle devenue cliché, Tavenne nous présente un exemple typique des rapports dégénérés entre image et objet – presque comme s’il s’agissait de démontrer à quel point l’image d’un objet peut devenir quelconque et égarer le spectateur. Par là même, s’opère la déconstruction de ces lieux communs dans le cadre d’opérations conceptuelles systématiques.

Parallèlement à ces « peintures de paysages » apparaissent, à partir de 1994, les premiers objets textiles monumentaux, qui sont souvent considérés aujourd’hui comme la partie la plus importante de la création plastique de Tavenne et en règle générale interviennent comme protagonistes dans ses mises en scène aux rapports thématiques foisonnants.

Les matières textiles mouvantes semblent effectivement être le matériau prédestiné pour les explorations que Tavenne entreprend à la frontière entre le bidimensionnel et le tridimensionnel. Les tissus peuvent à la fois être mis en valeur en tant qu’étendue plane dans l’espace ou en tant que volume modulable. Même si plusieurs siècles nous séparent du temps où l’art textile jouissait d’une haute estime en tant que discipline artistique à part entière, Tavenne fait référence à cette tradition de manière inventive avec les teintures et les montages en patchwork auxquels il soumet ses matières textiles. Et c’est précisément dans ce groupe de travaux que l’on trouve des recoupements particulièrement concrets avec sa biographie personnelle, car l’artiste n’utilise généralement pas d’étoffes neutres et neuves, mais des tissus usagés qui ont leur propre histoire. L’intérêt de Tavenne pour les textiles en tant que matériau remonte à un séjour dans sa ville natale, où il eut l’occasion de travailler sur un rouleau de lin ancien qui faisait depuis longtemps partie des possessions de la famille. A partir de celui-ci il décida de confectionner une sorte d’édifice, en se remémorant une petite sculpture en papier créée dix ans plus tôt et qui représente la maquette d’un pavillon composé de huit colonnes graciles et de huit segments de coupole. Une forme qu’il transposa alors dans une forme textile presque « grandeur nature ». Le séduisant paradoxe du pavillon réside dans le fait qu’il s’agit d’une architecture sans véritable utilité, dont la fonction consiste essentiellement à enjoliver l’environnement dans lequel se trouve cet édifice circulaire ouvert sur tous les côtés. Ici pourtant, l’archétype du pavillon emprunte à un vocabulaire architectural universel, et notamment aux formes de base éminemment symboliques du cercle et de l’octogone, ou à l’idée d’un espace centré. Mais cette « construction », dont les caractéristiques élémentaires devraient être le côté prévisible et la fonctionnalité statique, se voit privée de tout fondement avec la réplique en lin de Tavenne. L’enveloppe de tissu léger, qui s’affaisse et se gonfle mollement, conserve seulement sa forme (mouvante) grâce à un système de ficelles et de lattes auquel elle est accrochée comme une marionnette : on dirait le fantôme d’un édifice dont l’apparence éphémère n’est plus déterminée par son contact avec la terre.

L’année suivante, Tavenne passe à l’étape des sculptures-tentes autoportées (Zelt-Skulpturen) qui, dans la plupart des cas, sont accessibles au public. Dans notre imaginaire, les tentes sont associées à la forme d’architecture la plus primitive et ancienne parce qu’elles appartiennent à l’histoire de l’humanité depuis des dizaines de milliers d’années. Généralement ces habitations archaïques adoptent des formes géométriques simples, basées sur le cercle ou le rectangle, ce qui rejoint l’intérêt persistant de Tavenne pour les formes élémentaires plastiques. Comme une tente se transmet de génération en génération, son type ne connaît ni début ni fin (à l’instar de toutes les architectures nomades) ; du fait de sa réutilisation continue, sa forme est donc soumise à des modifications incessantes au fil du temps. Cette construction textile évoque des scènes de départ et de retour, des rêves de mobilité sans limites et de déploiement dans l’espace.

Avec ces objets-tentes, les comportements et les sensations du visiteur présent dans la pièce rejoignent également un thème souvent exploré par Tavenne. À l’intérieur de ses sculptures en tissu, l’artiste crée un environnement qui s’affranchit largement des systèmes de référence habituels ou des règles en vigueur dans le monde « à l’extérieur ». L’expérience de ces espaces est d’autant plus saisissante que l’enveloppe externe de la sculpture contraste vivement avec l’intérieur. Des tentes rapiécées et clownesques ou des tentes de cirque se métamorphosent au dedans en des espaces de méditation noirs profonds et dépourvus de lumière, tandis qu’une structure ronde aux dimensions généreuses est traversée seulement par d’étroits passages claustrophobiques en spirale.

Tavenne a volontiers tendance à associer plusieurs de ces objets textiles monumentaux ; il les rapproche et établit des liens formels et thématiques entre les sphères, les parallélépipèdes et les cylindres. Leur vue d’ensemble, avec les interférences entre ces différents corps spatiaux, fait prendre conscience de leur qualité picturale, que l’artiste souligne au moyen de la teinture et du montage des enveloppes extérieures.

En ce qui concerne le plan de ses tentes et, à partir de 1998, également le corps des sculptures, il se focalise sur la forme universelle du cercle. En tant que figure de symétrie maximale, le cercle est aussi sans commencement ni fin ; depuis la nuit des temps il est connu comme symbole de la perfection et de l’infini. Plusieurs sculptures sphériques de Tavenne font allusion à ces connotations du cercle souvent exploitées dans l’histoire de l’architecture occidentale. Mise en relief dans les cosmologies de l’Antiquité et du Moyen Âge, la signification symbolique des mesures et des nombres pour la relation entre l’homme et le cosmos semble jouer un rôle particulièrement important dans la conception de ces travaux.

Même au-delà des objets textiles, le cercle et sa fonction dans le code régissant les représentations historiques du cosmos semblent régulièrement attirer l’artiste. Ainsi, le noyau d’un groupe de travaux complexes développés durant de longues années se trouve dans un manuscrit du début du XIIIe siècle, une Bible moralisée (2) ornée de précieuses enluminures. On y voit, située en bonne place, une représentation de la figure du Dieu créateur qui, considéré à l’époque comme «bâtisseur du monde», ébauche le disque de la terre à l’aide d’un immense compas. Manifestement, l’idée que l’ébauche permet de déboucher sur l’invention – une notion remontant à l’Antiquité, où le processus de la création du monde est envisagé de manière distinctement rationnelle, voire intellectualisée – séduit tout particulièrement Tavenne. Dans un dessin à la gouache de 2001, l’artiste paraphrase le cosmos symboliquement créé par Dieu le Père : on y voit un élément circulaire doté d’une bordure verte ondulant de façon organique et d’une prolifération de formes intérieures sombres. C’est le point de départ d’une vaste série de travaux picturaux et sculpturaux. Avec une logique implacable, toutes les formes se développent dorénavant à partir de la figure si symbolique du cercle. Ses innombrables variantes graphiques, où des formations de rayons, vagues ou spirales se déploient sur la surface sous-jacente, évoquent avec une réserve apparemment délibérée la puissance des forces cosmiques ; la plupart du temps, une bordure colorée au contour précis vient cerner la forme sphérique générale. Dans plusieurs images, une figure intérieure aux allures de polype révèle que le cercle est la membrane d’une cellule au centre de laquelle se produisent des processus organiques imprévisibles et où émergent des emblèmes fantomatiques. Sur d’autres feuilles, des formes circulaires viennent composer des constellations planétaires fantastiques ou évoquent des trous noirs d’une profondeur incommensurable.

Les sculptures monumentales de ce groupe de travaux, également inspirées du disque de la terremédiéval, exhibent ostensiblement leur mode de production extrêmement élaboré, à la fois du point du vue conceptuel et technique. Avec le cercle comme origine, leurs éléments se combinent dans des configurations structurelles obéissant chacune à un principe méthodique différent. Les proportions insolites des différents composants sont dérivées de systèmes radiaux, de schémas de spirales ou de carrés qui par friction viennent contredire la forme générale du contour circulaire. Le format imposant de ces anneaux et disques est tout aussi remarquable que leur organisation structurelle. Deux fois plus grande que le spectateur, la «bordure de la terre» verte (Erdsaum) faisant écho à la création du monde biblique se dresse subitement devant lui, légèrement adossée au mur de la salle sous forme d’un objet tangible. Dans la même position, le massif anneau de bois à facette fait songer à un gigantesque cadre ou à un lourd portail. Enfin, le disque fermé d’un noir brillant reflète, suivant les méandres de sa structure intérieure, la salle d’exposition et le visiteur qui s’approche, tout en se présentant comme un trou noir aussi attirant que vertigineux. Les constructions discoïdales de Tavenne – qui, en tant que sculptures, explorent à nouveau les rapports entre la forme plane et les volumes spatiaux – permettent donc, à l’instar de cadres de visée, d’appréhender les idées et les notions que véhiculent les modèles cosmologiques dont s’inspire l’artiste. En 2005, Tavenne introduit un nouveau genre dans son œuvre, celui de la Psychokiste mentionnée au début : il s’agit d’un assemblage d’excentriques revenants de banals objets quotidiens et de curieux artefacts, que l’artiste expose dans des vitrines murales tendues de noir. Face à ces mises en scène indéchiffrables et curieusement maladroites, dont l’ambition encyclopédique reste néanmoins sensible, l’observateur est une nouvelle fois renvoyé à la question de savoir ce qui détermine – pour lui comme pour les autres – la perception de l’apparence et de l’être dans l’expérience visuelle et physique : toute connaissance et découverte compréhensible est basée sur la perception du monde à partir du point de vue du sujet. Les objets émergeant de l’obscurité entre les reflets de son propre corps deviennent visibles ou restent occultés selon le degré de superposition ou d’interpénétration avec le soi reflété. On ne peut démontrer plus clairement que l’image des choses et la création de leur réalité est déterminée par l’attitude que l’observateur adopte vis-à-vis d’elles comme de son propre ego.

(1) Emmanuel Kant, Critique de la Raison pure, extrait de la préface de la seconde édition (1787), traduction de A. Tremesaygues et B. Pacaud, Paris, PUF, 1975

(2) Bible moralisée, 1220/30, hauteur 34,4 cm, Vienne, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 2554, fol. 1v (Le Créateur).

The Tavenne model. About creating other places temporarily.

A table like that could become a palace, at least for the time being, transformed into the centre of an imaginary kingdom, and a curtain and the niche behind could temporarily offer sufficient protection against a reality that had clearly been present before – though a reality that in these precious moments scarcely seemed to be of any particular importance. And this despite the “grown-ups’’ feet sticking out under the table, the cramped space and the inadequate props, as well as all the other factors that made us aware of the limited nature of all the materials at our disposal, and of the fragility of these temporary constructs. The little kingdom under the table, that cramped refuge behind the curtain – especially in the way they were so magnificently taken for granted - could function as primal scenes for all the artificial paradises that we still want to secure for ourselves as adults, with incomparably more effort – produced with enormous physical, material or social application, and regulated as meticulously from the inside as they are jealously guarded against the outside world by bouncers, dress codes, conversational conventions etc. And all in the hope that reality will become different, and possibly more pleasant, at least for a certain time.

Heterotopias

Tents, pavilions, domes, spheres, some constructed from complex building plans with a carefully devised inner life, and some fitted together quite cursorily from a very few elements, have long made up the greater part of Vincent Tavenne’s artistic production, his sculptural œuvre, so to speak. Massive in their scale, literally of architectural dimensions, they take possession of interiors, but we are just as likely to come across them outdoors. They draw their particular quality from an impression of ambivalence that they subtly trigger in us. These objects seem both natural and contrived at the same time; their immediate presence also emanates an element of reticence, perhaps a reserved quality; but above all they are quite delicate, fragile structures in their immense and architectural monumentality, as obvious as they are mysterious. Probably even ‘economy’ is a suitable term to help us to approach this ambivalence, to pin down the effect these constructions actually make. Does not the idea of materiality, of weight and volume, of great effort in terms of planning and design crop up in the context of both architecture and sculpture? And is it not the case that Tavenne’s objects undersell their ideas – though in a fairly virtuoso way? If a gigantically voluminous sphere, for example, is created from a bit of material and a few strips of wood, if a highly dramatic stage landscape opens up before us or we are well-nigh crushed by tents and pavilions we can walk into, packed together in an exhibition space. Here it is immediately clear how commandingly Tavenne is calculating cause and effect, the necessary effort needed to create the desired effect (1). And that he is entirely aware how to impinge upon our state of mind when doing so. Incidentally, this makes it completely irrelevant to conduct a conversation about these works in terms of traditional art history, in order to distinguish the sculptural from the architectural, for example, and thus hold apart the idea of aesthetic autonomy and the concept of applied functionalism, or to position the role of the artist against that of a sculptor, thus proving the cultural added value of this project. On the contrary, Vincent Tavenne’s sculptural and architectural objects do present us with the gift, generous to a certain extent, of not having to start on the sanctioned cultural plane of cultural codes, but to begin with one that can – possibly unduly – be taken for granted: for example in the model disposition of solid and space. In that these objects make us aware of our state of mind, on the one hand in a confrontation as aesthetic ‘objects’ in justifiable juxtaposition, and on the other hand as common ‘situations’, into which these spaces, stages and arrangements draw us directly and physically. Admittedly without seeming manipulative: the fact is that they conceal their type, their mode of construction from us, despite all their refinement, all their creative sensitivity, just as they would be unlikely to present themselves as exclusive in matters of material and form. In fact a little timber and a little fabric are enough to create spectacular dimensions or fantastic forms, to invoke history or exoticism, to define an inside and an outside space with a simple linen cover and to create even more atmospheric specifics in this interior – tents that seem to come from the Thousand and One Nights, fragile pavilions with a well-nigh rococo elegance, entranced and exotically dreamy, complete with the fascinating play of light and the pleasantly tactile quality of different materials. This could sound like escapism, a regressive reaction to the prevailing conditions; like art as a hopelessly utopian search for salvation. Rather than that, I would suggest that Tavenne’s works should be seen as tangible models (in their dual function as real and reflective objects) for ‘other places’, and at the same time that they should be used as backdrops, and thus read metaphorically. This would show us the constructed nature of any kind of heterotopia without – and this could easily happen in the zeal of such working towards enlightenment – depriving us of the comforting prospect that such heterotopias might generally be possible, and it would also remind us that in fact we have the means of constructing (2) such different places at our disposal at any time.

Monter/Montrer

So visualization rather than escapism. No artistic paradises, but quite concrete models. Tavenne is also working in this spirit in his current work developed for a specific place (3). The fact is that “Monter/Montrer. Du proche au lointain dans l’escalier” (2008), a kind of textile tower, does not just occupy the stairwell in the Stuttgart Hospitalhof sculpturally; the work implants itself there as a model situation that can be read in various ways, addressing ascending and descending, inside and outside, accessibility and exclusion. This tower made of strips of different coloured material is accessible at its base, and it is possible to look inside the entire structure. It becomes brighter or lighter from storey to storey, thus giving the ascent itself a metaphorical quality – freely following the pattern of ‘per aspera ad astra’, for example. It fact it almost acquires the character of an initiation when the gesture of showing, ‘montrer’ in French, blends into the process of climbing, ‘monter’, as if in a distorting mirror, thus correlating movement and perception in a single cognitive process both represented symbolically and open to model-concrete experience. Which would make it possible to redeem, as is immediately comprehensible from this example, what we would generally wish to be the effect of a heterotopia that could be formed by the social consensus that is art: a tangible added valued within a reality beyond escapist projections, but without concern for the constraints of the prevailing circumstances – simply in the form of pure aesthetic experience, along with the awareness resulting from this.

From: „Vincent Tavenne – SENDER ÄTHER EMPFÄNGER“, exhibition catalogue RÄUME FÜR KUNST UND SCHOLZ, Hospitalhof, Städtische Galerie Waldkraiburg, Stuttgart 2008. Translation: Michael Robinson

Notes:

(1) 1 To say nothing of the pragmatism of technical production, as expressed by staging an entire exhibition out of the car boot, so to speak and being perfectly able, if it were to be necessary, to store an entire life’s work in the garage. (2) The heterotopia prevails – unlike the merely ideal utopia or the total disaster of the dystopia – in the here and now, without utterly and completely sharing the prevailing circumstances. On the contrary, it sets up its own conditions and laws. (3) The installation in the Hospitalhof is part of Tavenne’s “Sender Äther Empfänger” exhibition project, which extends over several venues within the city of Stuttgart.

Vincent Tavenne at Radio Athènes

Biography

1961 born in Montbéliard (France)

1983–1985 Studied at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with Ulrich Rückriem

1987 Stipendium deutsch-französisches Jugendwerk

1998 Piepenbrock Nachwuchsstipendium für Bildhauerei

1999 Villa Romana Prize, Florence

Lives and works in Berlin

Solo Exhibitions

2021

Die Abstellkammer des Universums, Kunstverein Rastatt

2020

R.U.N.D., Galerie der Stadt Backnang

INNER SP CE, Radio Athènes 27.03, Athens/Greece

2019

HIMMEL & HÖLLE, Fahrbereitschaft, Berlin

2018

Interaktiver Käse, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2017

„V.T.“, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens zu Gast bei Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

2015

Eine Vincent Tavenne Schau... eine Schau von Giti Nourbakhsch, Jarmuschek+Partner, Berlin

Nach woanders, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Weg nach weiter, M29 Richter & Brückner, Cologne (with Ina Weber)

CHEESE, statsion, Berlin

Weg nach Dort, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund, Germany (with Ina Weber)

2013

Code_n 13, Messehallenkonzept for GFT Technologies, CeBIT, Hannover

2012

Gertrud #2, Höhe x Breite x Tiefe, Sculpture installation in St. Gertrud, Cologne

Etroit, plat, mince (weit, tief, breit), Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2011

Déplie-toi! Entfaltung und Illusion, Städtische Galerie Bietigheim-Bissingen

2010

POLARISE-TOI, Saarlandmuseum, Saarbrücken

2009

SENDER ÄTHER EMPFÄNGER. A travers la stratosphère, Städtische Galerie, Waldkraiburg

MOI TOI ET TON MOI, Art:Concept, Paris

2008

SENDER ÄTHER EMPFÄNGER, RÄUME FÜR KUNST UND SCHOLZ, Stuttgart

MONTER /MONTRER – Du proche au lointain dans l’escalier., Hospitalhof Stuttgart

CONFUSION UND ILLUSION, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

ANSICHT EINER ABSICHT – ou le spectateur comme acteur, Kunstverein Lübeck / Overbeck-Gesellschaft

Hinterm Vorhang (Fremde am Tresen) (with Ina Weber), MÜLLER / SCHMIDT, Berlin

2007

ILLUSION UND SIMULATION: TROIS MACHINS, UN TRUC, DEUX BIDULES, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2006

Wer sind wir, wohin gehen wir, wie geht's dir?, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

2005

Black Hole, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

2004

VEHICULES WEBER TAVENNE VAHRZEUGE, M29 Richter & Brückner, Cologne (with Ina Weber)

Ansicht eines Anfangs, Kunstverein Arnsberg

2003

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2002

Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

2001

Hundert Fragen und keine Antwort, Kunstverein Braunschweig

2000

Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne

1999

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

1998

Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne

Piepenbrock Kunstpreis, Nachwuchspreisträger, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin

1997

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

La Signature des artistes, (with Joseph Zehrer and Uwe Gabriel) Nice Fine Arts, Nizza

1995

Forum Stadtpark, Prag

1994

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

1993

Friesenwall 120, Cologne

1991

Galerie Weikhard-Cassaignau, Paris

1989

Galerie Vera Engelhorn, New York

1987

Galerie Vera Engelhorn, New York

Group Exhibitions

2020

Bookies two, Galerie M29, Cologne

Zurück zur Erde, Laura Mars Gallery, Berlin

small is beautiful: (A)rtschwager to (Z)augg, Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich

Wolken in der Zeitgenössischen Kunst, Oldenburger Kunstverein, Oldenburg

2019

Alles auf einmal...und der Mond, Fahrbereitschaft, Berlin

haah25, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens at Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

haah25, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2017

14. RischArt Projekt: Parasympathikus, public space Kunstareal Munich

Katharina Jahnke und Jörg Wagner – Der unerklärliche Einfluss von, MATjÖ Raum für Kunst, Cologne

2016

Between two horizons. French and german avant-gardes of the Saarlandmuseum, Centre Pompidou-Metz/France

Schau III, Kunsthaus:Kollitsch, Klagenfurt/Austria

CAB 2016, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens zu Gast bei Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

2015

Schau II, Kunsthaus:Kollitsch, Klagenfurt/Austria

A blur, a beautiful blurry blur – curated and written by Giti Nourbakhsch, Galerie Karin Guenther, Hamburg

Achtundvierzig Zwölf, an exhibition with: Martin Gostner, Trixi Groiss, Hans-Jörg Mayer, Thomas Rentmeister, Ulrich Strothjohann, Vincent Tavenne, Iskender Yediler, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2014

and all together now, M29, Köln

UM-Festival 2014, öffentlicher Raum in der Uckermark

2013

2000+ Neu im Saarlandmuseum, Saarlandmuseum, Saarbrücken

360°: die Rückkehr der Sammlung, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

2012

Sammeln für die Zukunft. Kunst von 1952 bis 2012, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

30 Künstler / 30 Räume, Kunsthalle Nürnberg, Neues Museum, Institut für moderne Kunst and Kunstverein Nürnberg

Hasenstall, Galrie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

2011

Lumière noire. Neue Kunst aus Frankreich, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

2010

LARGER THAN LIFE – STRANGER THAN FICTION, Triennale der Kleinplastik, Fellbach

In good faith, M29 Richter·Brückner, Cologne

At Home is Where the Heart Is, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

2009

ECHTWALD, Galerie Giti Nourbakhsch, Berlin

Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux

2008

Prêt-à-porter, Kasseler Kunstverein

2007

Sammlung Grässlin, Räume für Kunst St. Georgen

2006

Memento Mori, Comme ci Comee ça II, Salon d’Art, Cologne

Sammlung Grässlin, Räume für Kunst, St. Georgen

abstract art now - strictly geometrical?, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

Nice Fine Art, Stadtpark/Städtische Galerie, Lahr

2005

Temporary Import, Art Forum Berlin

Petit fours, Comme ci comme ça II, Salon d’Art, Cologne

Via Senese – 100 Jahre Villa Romana, Fuhrwerkswaage Kunstraum e.V., Cologne

2004

Bookies, M29, Cologne

ZK. Drawings from Cologne, Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool

Tombola, Kjubh Ausstellungsraum, Cologne

2003

Action Button, Neuerwerbungen zur Bundessammlung Zeitgenössischer Kunst, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

2002

HOSSA - German art of the year 2000, Centro Cultural Andratx, Palma de Mallorca

Von Zero bis 2000 – Zeitgenössische Kunst aus den Sammlungen Grässlin, Weishaupt, Froehlich und FER neu präsentiert, Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe

2000

Skulptur 20002, Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven

Hey international competition style..., TENT, Centrum Beeldende Kunst, Rotterdam

Deutsche Kunst in Moskau, Moskow

1999

SUPERCA..., Stedelijk Museum Bureau, Amsterdam

Mondo Imaginario, Shedhalle Zürich

1998

Aller et Retour, Kunstverein Bonn, Stadtgalerie Kiel, Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken

Symposion, Icebox, Athens

1997

Transit, Œuvres du Fonds National d’Art Contemporain, École des Beaux-Arts, Paris

1996

Galerie Agathe Nisple, St. Gallen

Liste '96 - the young art fair in Basel, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Eröffnungsausstellung Hohenstaufenstraße, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

European Art Forum Berlin, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Glockengeschrei nach Deutz - das Beste aller Seiten, Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne (Cat.)

1995

Pittura immedia, Neue Galerie Graz

Kiron Khosla lädt ein, Galerie Grunert und Janssen, Cologne

1994

electric judge, Kreis 28 e. V., Innsbruck

1993

Friesenwall 120, Cologne

Grafica 1, Innsbruck

1992

covered uncovered, Galerie Kubinski, Cologne

1988

Halle Rückriem, Cologne

1985

Galerie Kleinsimlinghaus, Düsseldorf

1984

Galerie Mathieu, Besancon

Publications

2020

Edited by Martin Schick

Essay by Christel Fricke

exhibition catalogue Galerie der Stadt Backnang

german/english

24 x 18 cm

60 pages

2010

Essay by Kathrin Elvers-Svamberk

exhibition catalogue Saarlandmuseum Saarbrücken

german/english/french

32 x 22,5 cm

134 pages

Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfilden

2008

Essays by Hans-Jürgen Hafner, Xavier Zuber

Ed. Thomas Grässlin, Nanette Hagstotz,

Helmut A. Müller, Gregor Scholz, Stephanie Benzing

german/english

32 x 22,5 cm; 79 pages

Exhibition catalogue RÄUME FÜR KUNST /

Hospitalhof Stuttgart

2001

Edited by Karola Grässlin

german/english/french

27 x 21 cm; 48 pages

Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König, Cologne

Exhibition catalogue Kunstverein Braunschweig

2011

Ed. Alexander Eiling, Juliane Betz

german/english

28 x 21 cm; 232 pages

Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne

Exhibition catalogue Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

2010

Essay by Nina Gülicher

german/english

28 x 21 cm; 352 pages

Edited by Ulrike Groos / Kulturamt der Stadt Fellbach

Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne

Exhibition catalogue 11. Triennale Kleinplastik Fellbach

2006

Essay by Veit Loers

32 x 22,5 cm; 52 pages

Exhibition catalogue Stiftung Grässlin, St. Georgen

2006

Ed. Lida von Mengden, Theresia Kiefer

25,4 x 20 cm; 119 pages

Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld

Exhibition catalogue Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen

2003

27,9 x 24,4 cm; 120 pages

Kunst und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik

Deutschland, Bonn

Exhibition catalogue Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin