haah.de

Stephan Jung

Exhibitions

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

stephanrichardhugojung@gmail.com

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Hammelehle und Ahrens at Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Return

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Guten Rutsch ins neue Jahr!

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Neue Arbeiten

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Works by Thomas Arnolds, Tim Berresheim, André Butzer, Stephan Jung, Stefan Kern, Matthias Schaufler, Daniela Wolfer

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

nö

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

André Butzer, Kai Helmstetter, Isabel Kerkermeier, Markus Oehlen, Matthias Schaufler, Stephan Jung, Markus Selg, Vincent Tavenne, Ina Weber, Georg Winter

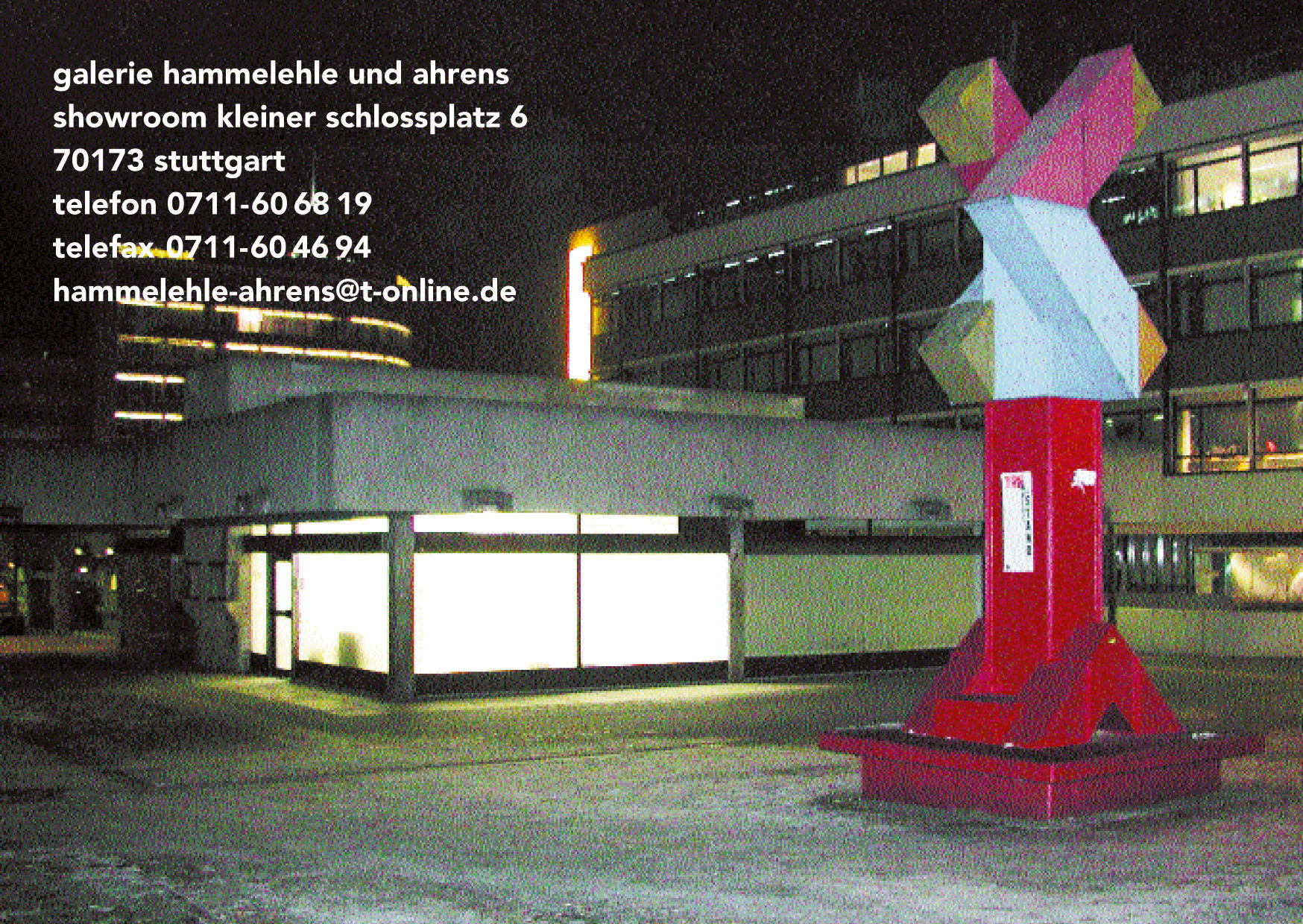

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart Kleiner Schlossplatz

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

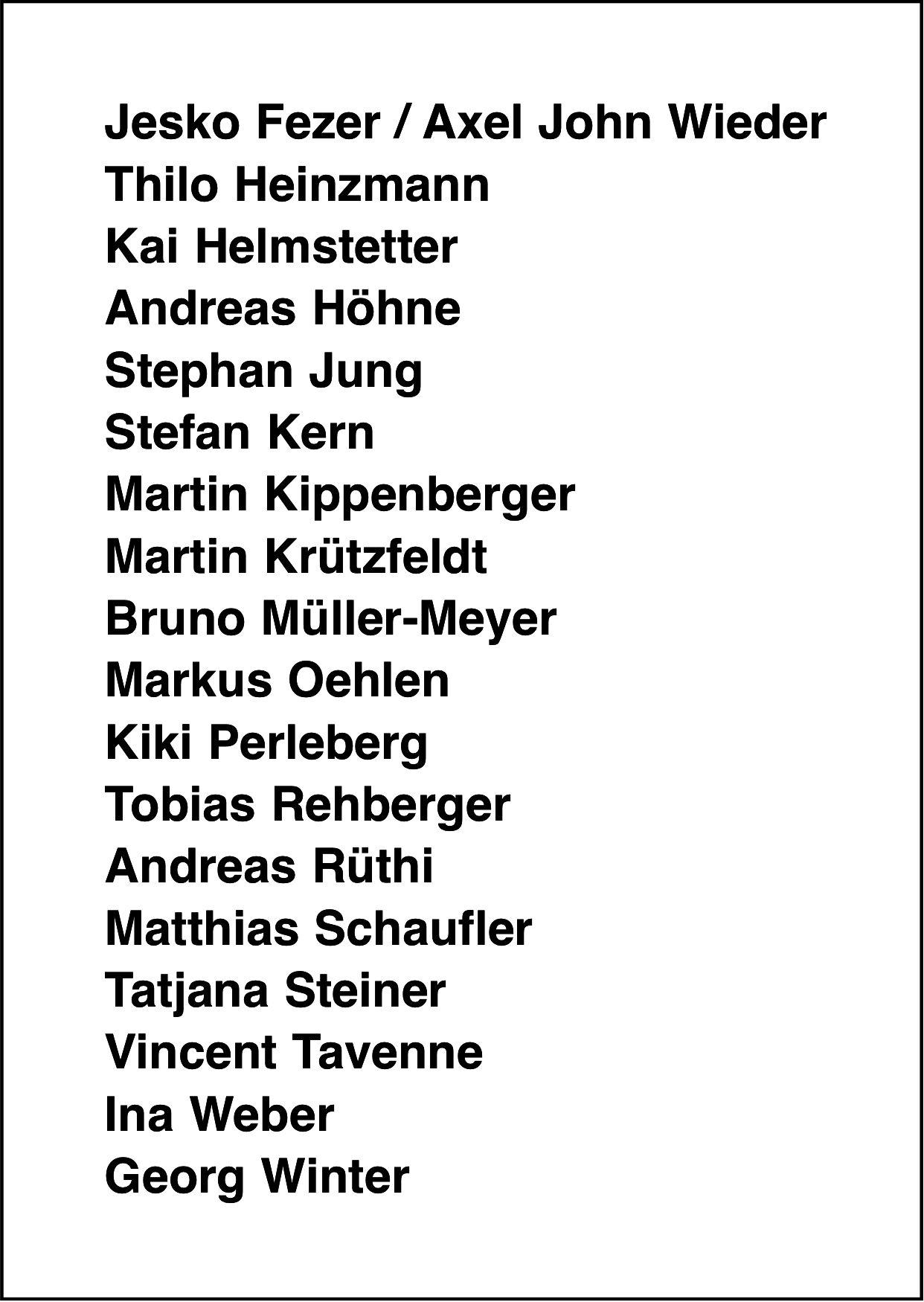

With works by Jesko Fezer and Axel John Wieder, Thilo Heinzmann, Kai Helmstetter, Andreas Höhne, Stephan Jung, Stefan Kern, Martin Kippenberger, Martin Krützfeldt, Bruno Müller-Meyer, Markus Oehlen, Kiki Perleberg, Tobias Rehberger, Andreas Rüthi, Matthias Schaufler, Tatjana Steiner, Vincent Tavenne, Ina Weber, Georg Winter

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

HOST

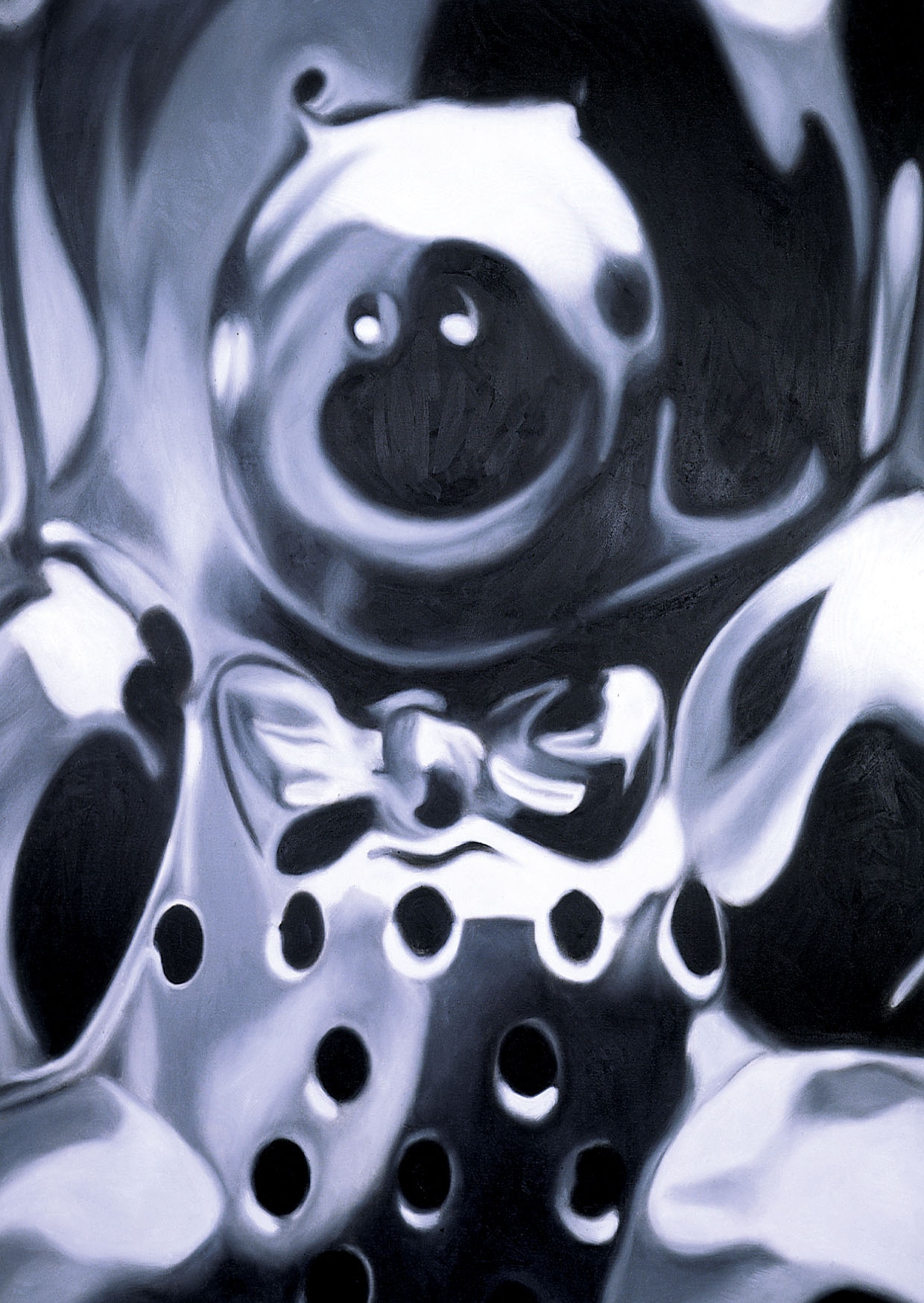

It is described as being similar to a flat spool for thread with a small wooden crossbar. “One is tempted to believe that the creature once had some sort of intelligible shape and is now only a broken-down remnant. Yet this does not seem to be the case; at least there is no sign of it; nowhere is there an unfinished or unbroken surface to suggest anything of the kind; the whole thing looks senseless enough, but in its own way perfectly finished. In any case, closer scrutiny is impossible, since Odradek is extraordinarily nimble and can never be laid hold of.” (1) The etymological vagueness of the name finds its counterpart in the ephemeral phenomenology of the thing. Obviously Odradek does not frighten anyone – that’s how the story ends, “but the idea that he is likely to survive me I find almost painful.” (2) For Kafka, Odradek’s bewildered existence seems independent of time and space – at least in the form we know them. It thus stands as an aesthetic figure for an indescribable reality. Indescribable because the figure is both abstract and concrete, present and invisible, wooden and yet alive, capable of using language, even though it confronts the world silently for most of the time.

Its extremely surprising freedom derives from being ‘of no fixed abode’ – and more than that, perhaps being immortal. “Can he possibly die? Anything that dies has had some kind of aim in life, some kind of activity, which has worn out; but that does not apply to Odradek.3 Odradek, the indefinable, the shadowy figure without an address, denies himself any purpose or expectation and resists something foreseeable. And essentially this justifies the family man’s cares.

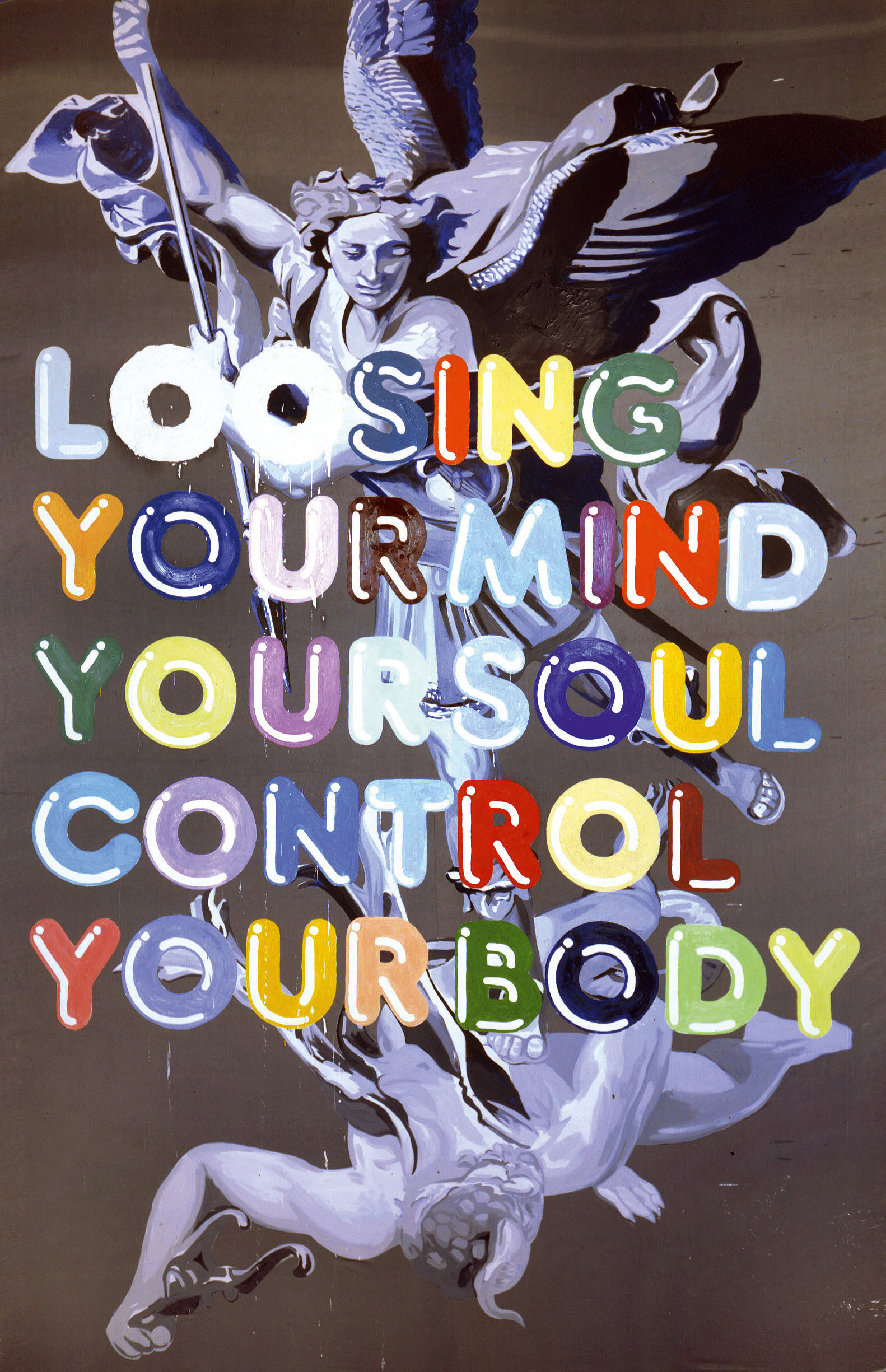

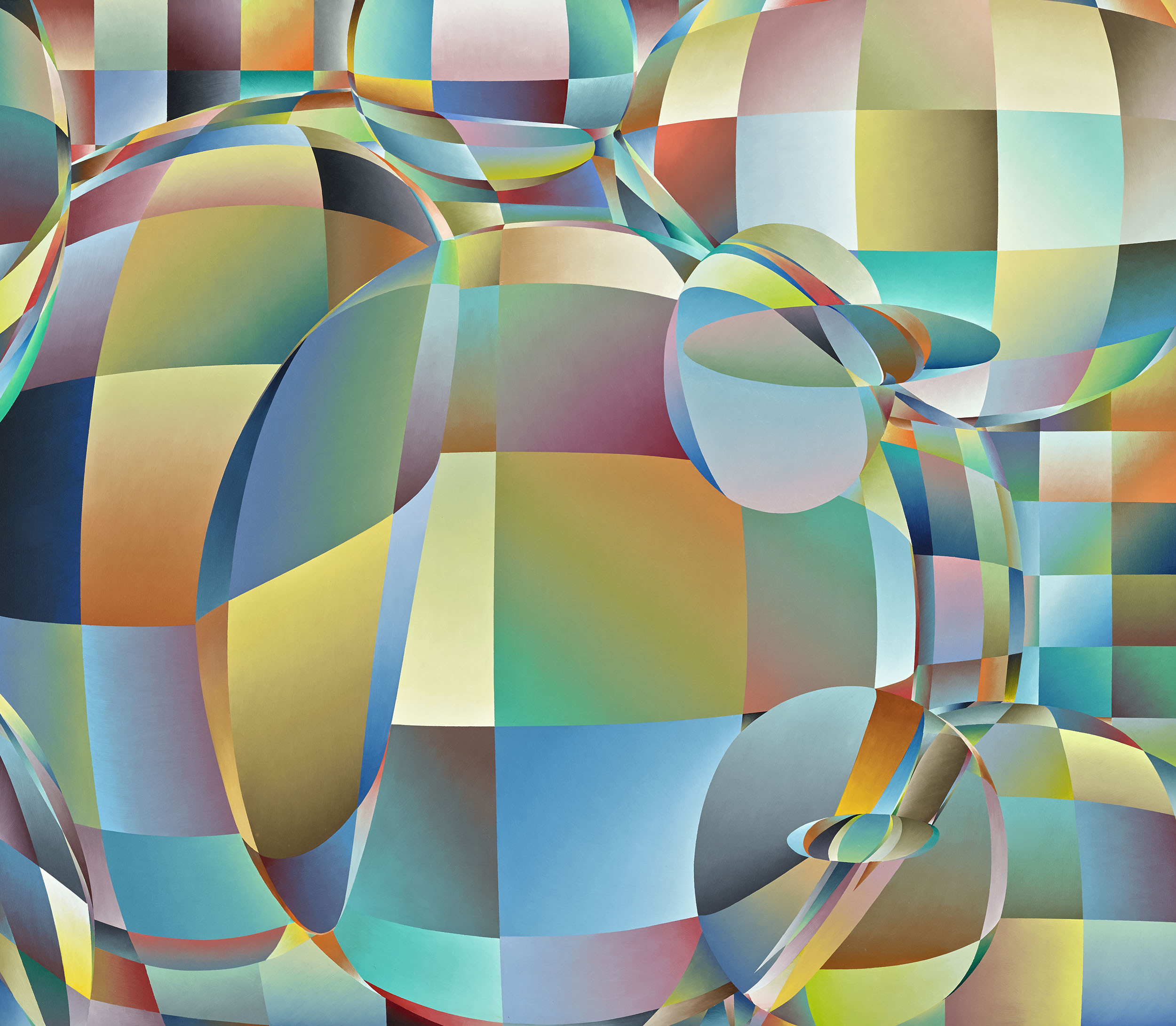

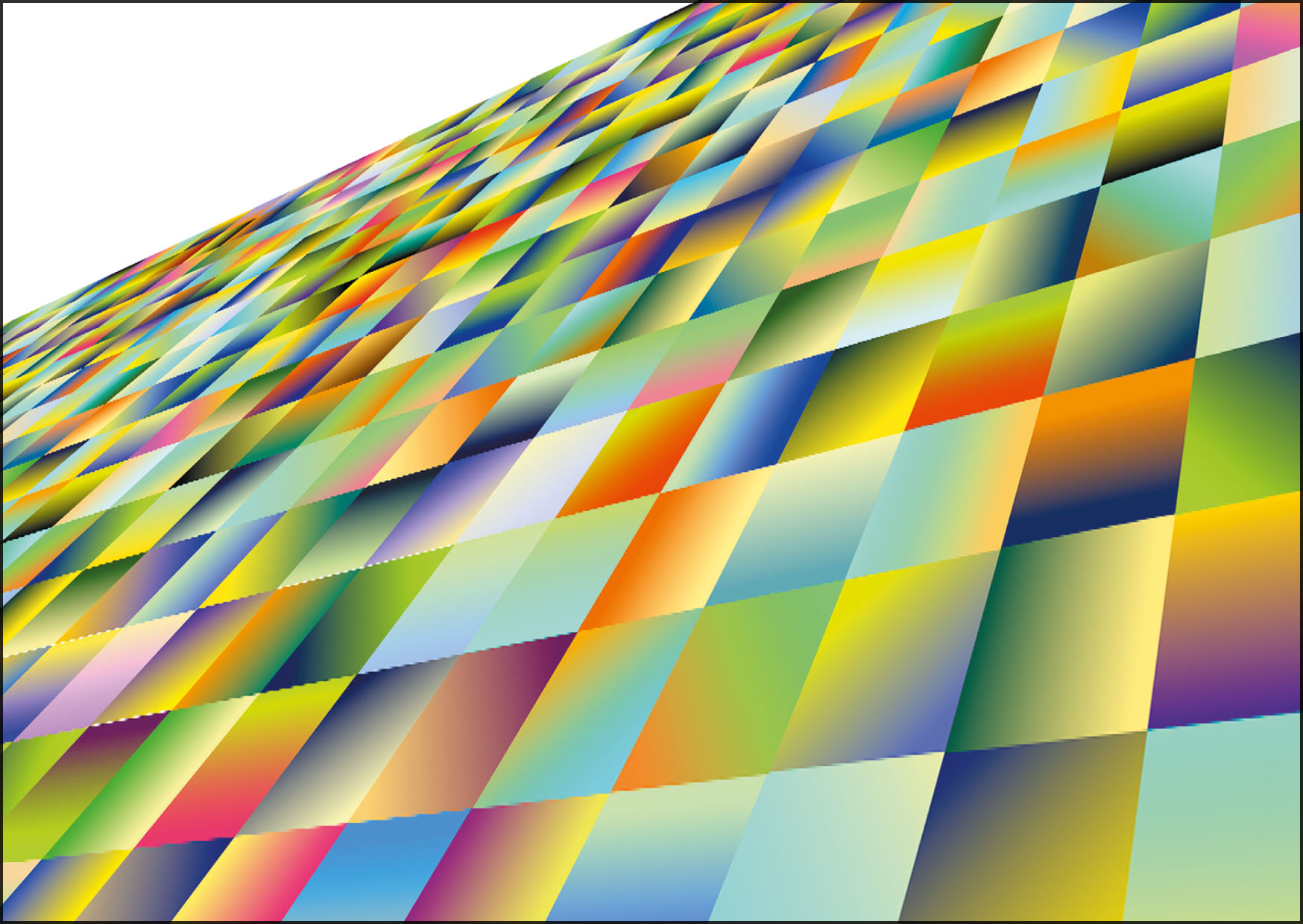

Stephan Jung’s images in his “Host” series open up a view of spaces that often cannot be grasped directly through the way they are depicted. To be precise: it is rare for a ‘complete’ space to be presented. Instead, fractal forms, or amorphous ones with mirror effects, create a visual impression with a three-dimensional impact. Evidence of alleged experiences of reality appears in a number of places: arrangements and objects that are placed in the images so that they can be recognized, and equally so that they can be demonstrated as artificial surfaces in the strange light of their appearance. An environment is captured in the dull glow of the surfaces that exists beyond their reflections and outside the limits of the pictures. Hence we are present in the illusionism of the painting and in the reality of the images. Large but shadowy, opaque and shimmering like metallic glass, a figure or merely a face is present in a number of the spaces. It moves towards us, silvery-cold, sometimes isolated and with no space around it, then filling the full format of the picture. The face is like a smoothly shaped façade. The eye cannot rest on it, but slips away all the time, and tactile contact will not encounter any warmth. The rigid features gain a semblance of life only from the fact that they reflect colours and forms. These bind the chromatically flashing mask into a world that does not isolate it completely, making it look dead. The figure seems to come from another world, and its presence is perfect to the extent that the painting can capture it.

Stephan Jung naturalizes an avatar in the medium of painting. It is Jung’s alter ego, and his representative in the artificially produced space that a software code made it possible to generate. So the virtual reality of an animation comes before the painting. This animation is qualitatively different from painting in that it operates with movement and thus creates an immersion that is alien to painting. Painting does not open any doors, but simply a window on to a different reality, whereas opera, theatre, film and now above all virtual reality invite us, with an almost breathtaking lack of boundaries, to leave the familiar, the known, behind in order to enter the fantastic structure of a new, alien, enticing world. A Net community’s so-called role-plays are not enormously popular for nothing: social interaction on an artificial basis permits a masquerade that conceals individual deficiencies. Actions do not really have serious consequences, and ‘wrong’ decisions do not occasion wounds for body and soul. You can always start again in a game.

But starting again is not the driving force behind Stephan Jung’s animation, nor is it escapism. In fact it is about reconstructing a past that comes to life again in the animation: the rooms the avatar glides through so silently are parents’ rooms, childhood rooms, and the house is of course the house where we spent our own childhood. If Jung were interested in role-play, then it would be the role-play of a singles player for whom the incipient doubling of the parental home is enough to make him a silent guest again. Social exchange and interactivity are not provided for in Jung’s animation, they are not present either for him or for his public. Without interaction, animation moves on the border between fulfilment and renunciation. Its invitation to step through the open door runs parallel with the experience of finding ourselves in a vacuum, without any direct action, room for manoeuvre or communication. While looking, we are suspended in a latent state of excitement, which does not lead to being either really active or passive. We accompany the avatar’s movement through the building in its shadow, but cannot control it, hearing nothing, only seeing. Stephan Jung’s restriction to embracing purely visual phenomena while moving, cutting out

the added value of sound, means that after continuing to share the experience the situation still does not become ‘natural’. In fact the impression that sound is unnecessary and only repeats the visual meaning of the image turns out to marginalize its function in truth: the world is not silent. Sound does convey an experience of reality in film, sustaining it, ideally synchronously with the image, in the necessary relationship between what we see and what we hear. (4)

So Stephan Jung’s animation could be seen as a trivial game, an episode, something that is not worth spending more than a few words on, introducing the avatar and its virtual surroundings as the image that provides the model for the painting. But the comparison between animated virtual reality and painted pictorial reality contains an artistically placed calculation, bringing the postmodern discourse about the experience of images and the loss of reality to a point in terms of precisely the difference that appears between the ‘agony of the real’ and the ‘emotional community’ of aesthetic perception: (5) Both Jean Baudrillard and François Lyotard identify a loss. While Baudrillard pins down the ‘agony of the real’ by stating that in mimesis as „combinatorial algebra … [it is no longer a matter] of imitation, of doubling, or of parody” but “… of substituting signs of the real for the real, i.e. of … dissuading real processes through their operational doubling, a piece of programmatic, error-free signalling machinery that generates all the signs of the real and of peripeteia,” Lyotard argues, following Kant: „When you painted, you did not ask for ‘interventions’ from the one who looked, you claimed there was a community. The aim nowadays is not that sentimentality you still find in the slightest sketch by a Cézanne or a Degas, it is rather that the one who receives should not receive, it is that he/she does not let him/herself be put out, it is his/her self-constitution as active subject in relation to what is addressed to him/her; let him/her reconstitute himself immediately and identify himself or herself as someone who intervenes… If a computer invites us to play or lets us play, the interest valorized is that the one receiving should manifest his or her capacity for initiative, activity, etc. … It implies the retreat of the possibility by which alone we are fit to receive and, as a result, to modify and do, and perhaps even to enjoy.” (6)

Thus Stephan Jung’s painting seems to function as a corrective, mediating between real things here and computer-based reality there. It is as though painting were fixing a pictorial time and a pictorial space that rescues the ‘charm of abstraction’ (7) for us today so that we can experience a here and now simply in contemplating; this is the necessary prerequisite for an aesthetic experience that existed before communication theory. (8) For painting, we can deduce, has no address, no fixed abode, it is not interested in those who identify themselves with painting concretely. It behaves more generally, referring only to all and to an observing subject that does not need to make itself known to painting through intervention. Its figuration, whether it derives more from the reality of an experience or the conditions of time and space, following exponents of the avant-garde, continues to retain an extremely surprising freedom, so that in the visiting performance of painting it can attend a process that is not to be concluded, extraordinarily mobile and merely to be caught.

Claudia Seidel in: “Stephan Jung – Host”, exhibition catalogue Galerie der Stadt Backnang 2005 (Translation: Michael Robinson)

1 Franz Kafka: Die Sorge des Hausvaters [engl. The Cares of a Family Man]. Stuttgart 1995. S. 189.

2 ders., S. 190.

3 ders., S. 189.

4 vgl. Michael Chion: Projections of Sound on Image, in: Film and Theory hrsg. von Robert Stam und Toby Miller.

Malden und Oxford 2000.

5 vgl. Jean Baudrillard: Die Agonie des Realen [engl. Simulations]. Berlin 1978 und Jean-François Lyotard:

So etwas wie: Kommunikation… ohne Kommunikation [engl. Something like: Communication… without Communication], in: Das Inhumane. Plaudereien über die Zeit. Wien 2001.

6 ders.

7 Baudrillard, S. 8

8 Lyotard, S. 133 f.

Biography

1964 born in Stuttgart

1985–92 Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Stuttgart (class of Joseph Kosuth and K.R.H. Sonderborg)

Lives and works in Berlin

Solo exhibitions

2017

Richard Hugo – stephanrichardhugojung@gmail.com, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2016

Stephan Jung, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens at Vickermann und Stoya, Baden-Baden

2014

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2013

Kunstverein Brackenheim

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

[...], Exile, Berlin

2011

Guten Rutsch ins neue Jahr!, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2009

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2007

nö, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2006

hell, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

God in Game, Galerie Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart

Galerie K4, München

2005

host, Galerie der Stadt Backnang

host 3, Aschenbach & Hofland Galleries, Amsterdam

host 2, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2004

host 1, Centro Cultural Andratx, Mallorca

elektrische, Galica Arte Contemporanea, Milano, curated by Alessandra Pace

2003

Aschenbach & Hofland Galleries, Amsterdam

2002

Kunstverein Leipzig

Hua Dong, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2001

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Kunststiftung Baden-Württemberg

2000

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Galerie Eigen+Art, Berlin

Galerie Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid

Atelier Jörg Immendorff, Düsseldorf

1999

Galerie Lotta Hammer, London

Galerie James Flach, Stockholm

Galerie Eigen+Art, Leipzig

1998

Neonarbeit im öffentlichen Raum, Jena

Kunstverein Lüneburg

Kasseler Kunstverein

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Galerie Eigen+Art, Berlin

1997

Galerie Eigen+Art, Leipzig

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Galerie Urs Meile, Luzern

1995

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

Galerie Eigen+Art, Berlin

1993

Ausstellungsraum Friedensallee 12, Hamburg

1992

Neonarbeiten im öffentlichen Raum, Berlin-withte

Group exhibitions

2016

Wendezeiten, KUNSTHALLE CCA Andratx, Mallorca

Light on, Kunststiftung Baden-Württemberg, Berlin

2014

Zuspiel, Kunststiftung Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart and Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart

2010

Colour Spaces, Galerie Münsterland, Emsdetten

2007

10 Jahre Sammlung Sal. Oppenheim, Bankhaus Sal. Oppenheim, Cologne

Unsere Affekte fliegen aus dem Bereich der menschlichen Wirklichkeit heraus, Galerie Sandra Bürgel, Berlin

Art Biesenthal, Biesenthal

2006

Abstract art now – strictly geometrical?, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum Ludwigshafen

2005

Galería de Arte Antonia Puyó, Zaragosa/Spanien (with Stefan Hirsig and Bendix Harms)

2004

Contemporary Art from Germany, Europäische Zentralbank and Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt/Main

Stay Positive!, Marella Arte Contemporanea, Milano

2003

Der silberne Schnitt, Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart

Action Button, Neuerwerbungen zur Bundessammlung Zeitgenössischer Kunst, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

New abstract painting – painting abstract now, Museum Schloss Morsbroich, Leverkusen

2002

REFLEXIONS, Monika Sprüth Philomene Magers, München

Showroom Kleiner Schloßplatz, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Stuttgart

2001

Offensive Malerei, Künstlerhaus Lothringer Straße, München

Figurações, Galeria Mário Sequeira, Braga-Portugal

Musterkarte – Modelos de Pintura en Alemania, Goethe-Institut Madrid, Galerie Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid, Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Madrid

Kunsthalle Göppingen

2000

Reality bytes. Der medial vermittelte Blick, Kunsthalle Nürnberg

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

1999

Paint/Land/Beauty, Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sunderland

1998

Galerie Philomene Magers, Cologne

Galerie Heinrich Ehrhardt, Madrid

1997

Ernst Museum, Budapest

Friedrich Petzel Gallery, New York

1996

Kunstverein Düsseldorf

Von den Dingen, Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen

1995

Technik/Techno, Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart

1993

Übungsgelände-Europa, der Nacken des Stieres, Exhibition project in Suhl

3K-NH, Linienstraße 146, Berlin

1992

Kunst kaufen in der Invalidenstraße 31, concept and realisation by Stephan Jung, Invalidenstr., Berlin

Publications

2002

23 x 16 cm; 48 pages

Exhibition catalogue Kunstverein Leipzig

2003

Neuwerbungen zur Sammlung zeitgenössischer

Kunst der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2000-2002

27,9 x 24,4 cm; 120 pages

Kunst und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik

Deutschland, Bonn

Exhibition catalogue Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin

2004

Essay by Allessandra Pace

english/italian

21 x 14 cm, 12 pages

Exhibition catalogue Galleria Galica, Milano

2005

Essay by Claudia Seidel

german/english

28 x 21 cm; 48 pages

Exhibition catalogue Galerie der Stad Backnang, Backnang

2006

Ed. Lida von Mengden, Theresia Kiefer

25,4 x 20 cm; 119 pages

Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld

Exhibition catalogue Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen