haah.de

Thomas Arnolds

Exhibitions

RUN

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

MARB7

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Kunstverein Reutlingen/Germany

LUFT

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Grad

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Kunstmuseum Bonn

Rausspazieren

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Works by Thomas Arnolds, Tim Berresheim, André Butzer, Stephan Jung, Stefan Kern, Matthias Schaufler, Daniela Wolfer

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens

Klinkerexpressionismus

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Behold the expanses, find one’s own, however far it may be

As insistently as consequently he demonstrates that an “absurdity” such as a painting can still concern and affect us, that painting lays into us as a relevant and timely form of expression.

A broader audience became acquainted with him during exhibitions like The luminous West at Kunstmuseum Bonn in 2010 or the newly-hung collection of Rotterdam’s Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in 2009. And as he already exhibited in Reutlingen in Wo ist hier? #1: Malerei und Gegenwart, we are glad to arrange his first institutional solo exhibition. Especially, because it preludes all upcoming presentations yet to be conceived and created for the Kunstverein by young, pioneering artists.

Personally, we got to know each other more than ten years ago when Tommy was still studying in Braunschweig. In due course we collaborated on our first exhibition but lost sight of each other, soon afterwards. Up until 2007 in Cologne when I found myself excitedly in front of some rather peculiar Lower Rhenish Clinker brick Expressionist paintings, a style I had not heard of in painting before. Soon, they turned out to be Arnolds’ first valid works, a fact that made me even happier than I already was on account of the paintings. From then on, we’ve kept close contact and continuously worked together for exhibitions and publications. However, what’s happened since?

At the outset Clinker brick Expressionism, possibly related to one’s own origins, to where one comes from, to memories of childhood and adolescence in the Lower Rhine area. Although seen painterly, Clinker brick Expressionism – a 1920s–30s architectural regional-style ranging from Westphalia to the Netherlands via the Ruhr and the Rhineland – extends a lot further. Above all, it’s about façade layout. And, bluntly put, painting upon the two-dimensional plane of a canvas is the very same thing.

Thus, Arnolds’ Clinker brick Expressionism does not at all present us with industrial buildings. In fact, we witness him tectonically opening up a thoroughly pictorial build-up. Witness him “raising” the picture plane from scratch, effectively, building it with individual elements brick by brick like a solid wall or façade situated right in front of us. By no means, we are confronted with a potpourri of Lower Rhenish motives. Quite the contrary, Arnolds conducts a painterly localisation preceding all biography.

Due to Clinker brick Expressionism he was able to grasp the fundamental dimensions, the elementary conditions of painting: height, width, depth, a painting’s basic directions, the jutting or recoiling, once tender, once rugged relations of colours and contrasts, the proportionality between all pictorial constituents, matter-of-fact statics, bulky dynamics and their considerably calculated, planar equalization in rigid grid-patterns, oppositional structures, or elaborately delicate textures.

While working on these paintings, he was thinking about the pyramids, he recalled.(1) A question of form: how to harmonise and mould small and unrelated particles into form, on barren terrain, against all odds? How to create consistent and enduring “monuments” from barely nothing? Opposed to all doubts with which the 20th century disputed painting, this is a decisive avowal for it. No “exit from” but an entry into painting.

The lifeworld, our world, is brought back into painting, in succession of Clinker brick Expressionism set in motion by the Kitchen-paintings. The outside world is strikingly transferred into the interior space of painting, real concreteness becomes non-objective chromaticity. After all, painterly “matter” never merged with its objective, motifal meaning. Accordingly, if Arnolds paints his own studio, it’s not a matter of naturalist depiction but a simple occasion. He couldn’t care less about the imitation of a world all too well-known to us. A private kitchen is »almost an awkward subject«, so banal and insignificant that maybe just because of this »at last painting«(2) emerges from it, as he once hoped. No more motifal deciphering but embarking on seeing painting itself.

Hence, we see strictly orthogonal interiors built with nothing else than the primary colours red, yellow, and blue. In its consequence this overstated exaggeration brings us little by little to see the thoughtfully balanced and levelled-out relations between colours, planes, structural grids, bands, and partitions as well as any other elements. What we see is »painting and not at all [Arnolds’] own kitchen«(3). The alleged home economics smartly turn into pictorial economy, house rules become planar order.

Considering the primary colours, it’s as obvious as the picture plane that Arnolds accrues from Piet Mondrian and De Stijl. For the primaries are the sources of all chromaticity and in such of every painting, too. Implying no reduction or restraint on the palette, they establish an enormous space of possibilities, instead.

Aside a faithful representation of reality Mondrian intended to reinstate painting’s very own and self-expressing means (plane, colour, form) as painting and reality are entirely different entities. Anyhow, among the pictorial reality alien to us there are things to be found equivalent to our world, to our interaction with each other, to our relations and proportions: what’s on top, what’s below, what’s circumstantial, things mutually battering or appealing to each other and so forth. By equalizing these contrasts and confronting us with them painting gives fresh impetus to us to reconsider our place in front of a painting or within the world and thereby gaining halt and stand for ourselves; without the need for recognizing any representational motif.

Arnolds absorbs and embraces Mondrian’s reflexion on the pictorial possibilities as well as Henri Matisse’s »purity of means«(4). (on the edges, Klee, Miró, or Picabia can be spotted) Once, that’s settled – and the primary colours are such clarification – he leaves the interiors behind and, in the following Stolling-paintings, definitely steps out, entering the rough expanses of the plane itself.

While the kitchens were dominated by frontality, the Strolling-paintings appear as views from above, topographical plans, or maps with countless, primary-coloured lineatures pervading the white and black pictorial fields like traces. Although, trace is not the most accurate term. Constantly, we’ve got the feeling that these lines are not the result of a bygone movement. Rather, we are seeing the vivid and immediate activity of colour always happening “just now”. Arnolds paces off the plane along protrudingly vibrant bands of colour, granting a firm, albeit tensely situated position to all things. Everything unfolds upon the plane, grounds, forms, and structures are inseparably “embedded into each other”(5), thus, while strolling even the figure / ground-problem dissolves practically into thin “air”.

At the same time as André Butzer, Arnolds expands his chromaticity by another primary colour in the °-paintings – “nude” or skin colour. The former presented his “Colour theory” in London: four huge paintings, three in red, yellow, and blue and a fourth one in flesh colour. Contemplating what painting is capable of, the necessity to augment the three, pure primary colours with a fourth, humanly existential one dawned on Butzer.(6) No matter how virtual it may be, painting is a permanent realisation, making present things absent, it is an embodiment of things and persons that are actually not there. Not without course flesh colour has been called incarnate. With most different preconditions both Arnolds and Butzer parallelly come to the conclusion that the biblical incarnation – becoming flesh – is always inscribed into and assigned to painting.(7)

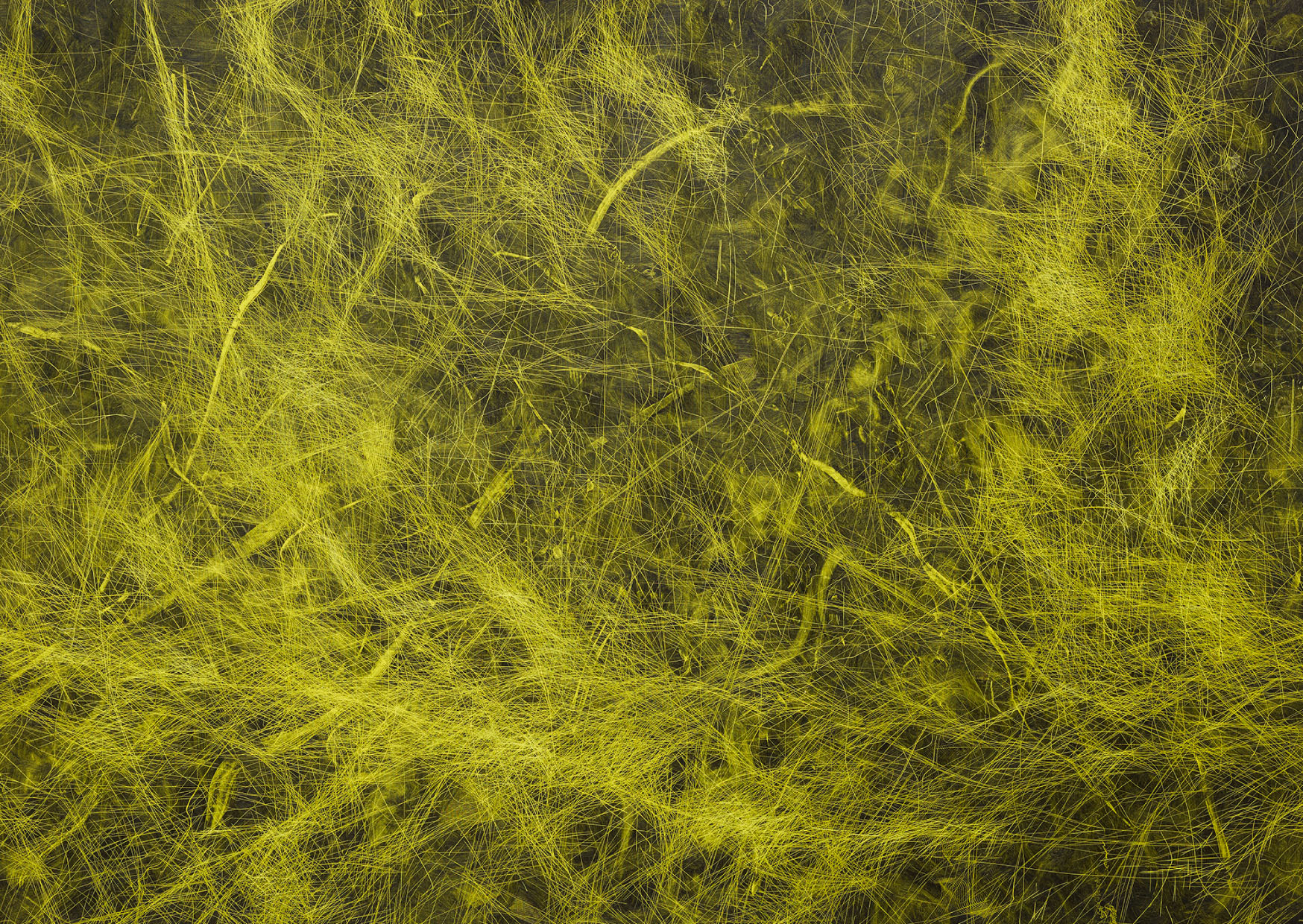

Thereby, Arnolds finally gathered both the formal and colourous vocabulary to venture into his Air-paintings in 2012–13. Forms and colours loosen up, the pictorial field widens. Severely, Arnolds acts out the oppositions between close and clear visions, between the pull into depth and the impact of the flat picture plane, between single colours and the colouristic whole, between tight geometry and fulminating planar ornaments, between non-objective, pure colour and almost unspeakable, “impure” congeries (a sudden orange, violet, or even green), between meticulousness and impropriety, between sincerity and folly. Yet, even these “indecencies” are well calculated, consciously applied, and united in a non-yielding pictorial whole.

Tying in with this, he has created more than 20 purely white paintings for Reutlingen, during the last year. The harsh chromaticity reverts into bright white and in the process something staggering takes place. The pictorial fields turn into sites of sheer emergence: upon the same plane massive forms, most subtle textures, and structures emerge from the very same colour, appearing as indetermined particles of expression, prior to all meaning or objective attribution, in the glistening self-light of the white. The paintings reside in this abeyance, reconciling line and colour, and displaying their gradual construction while being seen. They reveal how from isolated elements at first new words, then coherent sentences and at last a complete language evolves – ever on the boundaries of austerity and kicked-over traces, of striking signals and meaningless signs.

That’s the whole point. For any painter the question is how to attain one’s own language, one’s own painting, constantly new and still constantly the same. Accordingly, Arnolds both challenges and invites us: to regain the paintings as paintings again, to behold painting itself. Many contributed to the success of our exhibition. First and foremost we want to thank Thomas Arnolds for the delightful collaboration and the reality check his white paintings give us.

notes

(1) Thomas Arnolds in conversation with CM, Cologne, January 25, 2014

(2) Thomas Arnolds in conversation with Wolfgang Brauneis, in: The luminous West. A site assessment of the art landscape in the Rhineland, exhibition catalogue Kunstmuseum Bonn, Kerber, Bielefeld 2010, p. 138

(3) ibid.

(4) e.g. Henri Matisse, »The Vence Chapel«, in: Henri Matisse – On Art, ed. Jack D. Flam, Diogenes, Zurich 1982, p. 226: »examine every element as such within the pictorial construction: drawing, colour, the values, composition, and how these elements are united without diminishing one’s expressiveness by another’s presence […] that is to say, by respecting the purity of means« [translated by AS]

(5) q.v. Leo Steinberg, »Jasper Johns: the First Seven Years of His Art«, in: Other Criteria. Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art, UCP, Chicago 2007, pp. 17–54

(6) see André Butzer, Farbtheorie : Colour theory, exhibition catalogue Alison Jacques Gallery, Art Quarters Press, London 2010

(7) furthermore, Christian Malycha, »You cannot picture a likeness of N«, in: André Butzer – Probably the World’s Best Abstract Painter, exhibition catalogue Kestnergesellschaft, Walther König, Cologne 2010, p. 76–95

The Year Pink Broke

The invited established artists — all of them originating from the Rhineland or closely associated with it — from Isa Genzken to Andreas Gursky, in turn each had a younger, relatively unknown artist in tow. In the case of Arnolds, Albert Oehlen was the godfather. The exhibition extended over the whole museum, so that all involved parties each had a separate hall at their disposal. Thomas Arnolds took advantage of the available space and, for the first time, showed several of his 250 by 400 cm paintings that are consistently kept in red, yellow and blue. Six of them already existed when The Luminous West opened in July 2010 and a seventh (kochen) was completed in the fall — marking the conclusion of this series that began in spring 2008.

Two of the three so-called “Küchenbilder” (Kitchen paintings) were exhibited during the Art Cologne. Küche 1 hung in the group show My Generation, which was organized in the Spichern Höfe. On display is a schematic and consistently two-dimensional representation of a kitchen situation, executed in an accurate, even meticulous characteristic style. One believes to recognize (carefully worded) accordingly typical furniture and utensils, such as a cupboard, a sink or a stove, a pot, a pan or a spatula. The lower half of the yellow-framed painting is maintained primarily in red, while the color blue is dominating its top half. In addition to the alleged refrigerator in the lower left area and the delicately articulated segment in the upper right corner that is reminiscent to a brick-wall, there are only a few small areas that shine in bright yellow, such as parts of a pot or the face of a matryoshka. Both seem to be placed on a shelf that additionally represents the horizontal center of the image. Just like the fridge, the (at least mostly) yellow sink (including faucet and drain pipe), the blue cup and the mainly blue pot and all other items on the lower half have been applied to the red background — taking into account that “background”, given the strict abandonment of perspective constructions, in this case refers exclusively to the painting process itself. Since the entire canvas is primed evenly, the mostly red representations of utensils surrounded by large blue fields as well as the struts above the horizontal axis are the results of recesses.

Küche 2 was exhibited by Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens in a single presentation of Arnolds work at Open Space, a section of the Art Cologne. In addition, the painting was representing the three Kitchen paintings in the exhibition in Bonn. All of the items already found in Küche 1 reappear here, identical in number, form (at least their outlines) and proportion. At the same time, differences in the surface design of each item can be identified in their composition and color. Thus, a bowl-like vessel supported by two swan figures is no longer placed on the alleged refrigerator, but on the door lintel, while a schematic flat dish has moved down from the shelf onto one of the lower cabinets. Otherwise, the distribution of the objects to the upper and the lower half remains the same. Regarding their arrangement, the situation is quite different. The distinctive door is no longer cropped by the right edge of the painting, but has been moved toward the center and traces the painting’s horizontal centerline with its left edge. This in turn, to give another example of this rearrangement, leads to the sink being placed to its right and no longer remaining between the cabinets. The proportions between the three primary colors are more balanced than in Küche 1. Now there are large, red patches that divide the upper half of the yellow primed canvas. The structures beneath the shelf have mainly been painted, just like the door, in deep blue, the color of the frame. The vertical, rectangular area outlined in red on the door offers a view on the literal space behind it: a vertical rectangular yellow-painted piece of canvas. There, the outlines of a schematic bulbous bottle (a raised thin line that has been applied yellow to yellow) clearly stand out from the image carrier.

Also in the third Kitchen painting, those regular color bars are — just like the only fingernail-sized but very thickly applied oil paint accumulations — used as the internal structure of some monochrome fields. Some details of the first two pictures’ design principles are being maintained, for example in the case of the placeholder for a curved door handle or pearls lined up on the pot. In other places, such as the cabinet or the work surface’s triangular supports, these small paint accumulations have been rearranged. Again, other forms of surface design have been applied in a variable manner. In connection with Küche 1, a segment has been already mentioned that seems to represent a rectangular brick-wall by the regular arrangement of rectangular fields in rows. It is precisely this small-scale pattern that adorns the “refrigerator” in Küche 2 and that now structures the two tall rectangular “cabinets” in Küche 3. It is executed in the same bright yellow as the color in the painting’s top half, this time letting the primer shine through. The fact that the latter is rendered in blue remains in the interest of the internal thematic, motive and color unity of the three paintings and the same applies for the red-painted frame. In general, the topics of control system and variation, as well as rhythm and repetition, succession and stratification are of essential importance in Arnolds’ paintings. All work stages — starting from the paint application to the composition of each painting to the compilation of works — are based on these principles. This takes effect since the group of works Ich mach klar Schiff (I’ll clear the Decks) and Klinkerexpressionismus (Brick Expressionism), both from 2007. The three other large-scale works that have been shown in Bonn are, as the Kitchen paintings, primed in red, yellow and blue in chronological sequence: Schrank (2008), Spazieren (International) (2009) and schlafen (2010). Forty years ago, Barnett Newman asked — together with four of his paintings — the now legendary question of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (1966–70)). It rarely seems to have been denied with greater conviction than in Thomas Arnolds’ presentation in Bonn — certainly, shortly before, by Imi Knoebel, who has even titled his 2009 Berlin exhibition of new works in primary colors with the programmatic reply “ICH NICHT (I’M NOT)”. In the decision for or against figurative representation lies the most obvious difference between their approaches.

Concerning Schrank and schlafen, but also — albeit quite a bit harder to decode — Spazieren (International) Groß 1, it is a matter of supposed interiors. “Supposed” because the represented objects — some of them familiar from the Kitchen paintings’ sphere of living — are only a means to an end, or, as Thomas Arnolds calls it in the too short interview in the Bonn exhibition catalog: “occasions for painting”. Needless to say, that in an art historical sense the West began not to be luminous only after 1945. Jürgen Harten is also contemplating the modernity of the first half of the century in the detailed catalog essay. He examines art and art education in the Rhine and Ruhr area in the past 100 years. Artists such as Max Ernst and August Sander are being considered next to groups of artists such as “The Young Rhineland” or the “group of progressive artists” by Franz

Wilhelm Seiwert, as well as the legendary exhibitions of the 1910s and 20s (Werkbund exhibition, Sonderbund exhibition, Pressa). The presentation itself was not taken into account in the period before 1945; the same applies to the 50’s. The pillars — or pillar-saints — of presentation were five men who, with the exception of Joseph Beuys, intervened in the art world during the 60’s, namely: Imi Knoebel, Blinky Palermo, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter. A wider range might have lead to interesting situations — regarding the background of modernist reception of the work of post-postmodernism’s artists that Thomas Arnolds can be counted among.

“We want to do simple work beyond all chattering spirituality. Since we are only painters, sculptors, we begin with us, we start where non-random events began happening to us. (...) We know that there is no reality that can be confused with the reality of the painting, the sculpture. That is why we want to let the reality of the painting, the reality of the sculpture clearly become a reality—so that no one can confuse them with another reality anymore.”

Modernity has long since not merely served as a reservoir of signs. Rather, contemporary artists tend to address and refine its inherent methods and issues. Unlike the production of art in the 1980s and 90s, the formal aesthetic achievements of modernism are now being recognized more frequently instead of only being suggested. They are being updated instead of broken ironically. For Thomas Arnolds, painting itself is the paintings’ actual subject, and it is merely the history of painting that provides the framework, whereby the representations can be determined more accurately beyond their purely physical properties. A comparison of the painted with an extra-pictorial reality is therefore not an issue — not to mention a subjective, empathetic processing of an individual environment as a starting point. Once the sketch is being executed and once the outlines are being set, there is no looking back at “reality”. The negation of a representational function does not imply, however, that the pictorial surfaces mark a transition to transcendental spaces — in contrast to, for example, much of the color field paintings of the 1950s and ’60s. It is not the production of optical illusion, but the study of the painting process itself that is essential. Accordingly, spatiality is primarily intrinsic to painting — that is with regard to relevance of the manner of paint application. It is the latter — partly in relief-like execution, supported by the consistent two-dimensionality of the representation — that is responsible for ensuring that the painting is literally a space that opens toward the viewer. Hence, reflection instead of contemplation. In addition, an immense effort can be deduced from the controlled characteristic style that avoids any expressive or grandiose gesture. Here, painting is not only the subject in a conceptual way (as a specific, historically matching form of imagery), but also in a material way (as a particular option of image production).

“Seiwert’s commitment to the Haptic in art is deeply rooted in his interest in craft. In regarding art as a craft, Seiwert found the basic principle to render the internal, formal properties of a medium serviceable for a political statement. (...) The Cologne Progressives insisted not only on a painting’s craftmanship, but also on its “legality”; art was supposed to take place under very specific laws and rules. Here, law refers to the artwork’s material means, meaning surface and structure, and was supposed to contribute to a better readability for the viewer. Consequently, Seiwert spoke out against each work of art that conceals its inner formal “laws” by camouflaging how it has been made, be it a painting or a sculpture.

Lynette Roth, Painting as a Weapon: Seiwert – Hoerle – Arntz, quoted from progressive cologne 1920-33. seiwert – hoerle – arntz, Cologne, Museum Ludwig, 2008, p.15-132; here p.33

The paintings are closed off, they literally reject the rapt absorption into a transcendental depth, but they also refuse a certain scrutiny that primarily dedicates itself to the juxtaposition of an existing environment — whether concerning real space or spaces of memory. Only at first glance, the question arises whether, in the case of the Kitchen paintings, the two elements directly under the “countertop” are actually supporting columns or oversized illustrations of the letter A. On closer examination, it becomes clear that this polar question does not need to be posed, because the answer is: probably neither nor. In fact, in the painting’s lower half below a wide, horizontal strip, two shapes can be seen that result from relatively thin lines. One of them opens in a v-shape bent toward the bottom of the picture margin. The other — centered within this segment and positioned parallel to that strip — is almost extending towards the two diagonals. But there is no contact, neither between the lines nor between the peaks of the curved lines and the horizontal stripes. Any interpretation comes to

a standstill when the monochrome primer prevents a contingent representation of individual shapes. This form of semiotic versatility can also be observed in several other paintings. Thus, the three thick blue lines that appear to result in a small h or a chair in side view in the left upper corner of Spazieren (International) Groß 1, are also not being linked. However, also in this case, the lines (in this case yellow) do not outline the areal extent of the individual elements, but in turn result from exactly this area. There are not only objects but also lines produced by recesses. Here, the hierarchical separation of line and shape, thus of form and color, which has been touted by Modernist painting (also in its abstract branch) is turned upside down. “The surface”, as formulated by Arnolds himself, is “forced to the line. Absolute surface density up to the formation of lines.” In obvious contrast to the protagonists of color field painting, which in the 1950s, led by Newman, have been declaring an attack on those traditional hierarchical assumptions of image production, Arnolds’ work can be identified as non-representational only at second glance. Rather, it is a matter of paintings that no longer care about the traditional separation of figurative and abstract painting and that understand this claim as well.

“AM: Do you think that the differentiation between abstraction and figuration is no longer valid?

AO: From the artist’s point of view, I think that is so. But viewers still react differently to pictures with recognizable elements and those without.

AM: I have noticed that images reappear in your recent paintings and sometimes in an offensive way (I refer to the German flag of FM 38, or the woman’s breast in 223 (fig. 5)).

AO: I see these pictures as abstract ones. The figurative elements that are in them sometimes have no meaning and are not quotes. They are an element in the composition. Not in the sense of organizing the space. More like a flavouring of the brew. They are meant to bring cheapness, stupidity or pathos into the picture.”

Anne Montfort in conversation with Albert Oehlen, August 2009 quoted from Albert Oehlen. Abstract Reality, Paris, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, 2009, p.I-VI; here p.II

It is quite strange: For some time the (admittedly somewhat unusual) term “post non-representational” has been circulating — a term that Albert Oehlen himself has launched as a slogan for his approach to image production since the early 90’s. The fact that he dismissed it as “silly” in an interview in 2004 should not deter a number of authors from picking it up again. Not only that, it seems as if the two adjectives are always used in tandem, of course without comment. The artist provides the definition with a loophole — what more could one want? The term is apparently so silly that the effort of an interpretation does not pay off. But at the same time, it is not absurd enough to be deliberately ignored. Without doubt, “post non-representational” sounds, if not silly, yet somewhat bumpy — whereas the whole thing can now appear in a somewhat different light, considering neologisms such as “post-ironic generation” (to whose representatives from the Rhineland an exhibition in Leverkusen was recently dedicated). The term is not so inappropriate for a first attempt to characterize Oehlen’s “painting about painting” in general, and to overcome the categorical separation of figurative and abstract (ergo representational and abstract) painting in particular. At least it entitles the purpose of letting the painting emerge from the grip of static, i.e. dialectical and additive principles. To what extent this project is limited from the outset, is another matter.

In the context of his paintings, Thomas Arnolds likes to refer to “brush-stroke induced hard-edge painting”. Just like “post non-representational”, “brush-stroke induced” is also an extravagant and certainly — caution: pun alert — a somewhat thickly applied neologism that also transcends the characterization of Arnolds’ own work. “Post non-representational” is of course referring to Oehlen’s own work and primarily defines a crucial period: his departure from figurative painting at the end of the 80s. In addition, however, a diagnosis of the condition of contemporary art in itself resonates within the term. Specifically, it offers the option to leave behind the post-modern reference system with all its strategic implications (ironic comment, fragmentation, taboos, etc.) and to liberate the project of painting from its self-referential dilemma while remaining within the historically sanctioned dualism of figuration and abstraction. By the beginning of 00s years, when the “New Leipzig School” with its German-style neo-conservative backlash internationally succeeded, it became clear that this message has not even advanced up to the national borders. This approach to painting proved to be tightly post-modern—especially in its offensive outmoded habit. Against this background, one could interpret the term “brush-stroke induced” not only as idiosyncratic, but also as a key to a modern, i.e. post-post- modern understanding of art. The (over) emphasis on a specific and the focus on a differential characteristic of this particular form of image production encourage denying the final status of a supreme discipline to painting. The belief in the latter (respectively, the longing for warmth or just for perplexity) is, strictly speaking, still the necessary condition for the success of autonomous figural, or, to speak with Oehlen, nameable representations.

“AO: The joke is, of course, that the conception of the painting would actually like to be the contrary — and it hopefully is — of what you do verbally when you talk about the paintings. Then, in order to distinguish the paintings of one another, or to be able to prove what one is talking about, one says: the one with the poster or the one where the breasts are pictured. But the joke concerning a painting is that it is just the opposite: that the act of painting itself pushes itself forward, that the beginning and the end of the painting is the act of painting itself and that it gets the nameable things under control and that it possesses power over the nameable elements. And if the painting would work in reverse —i f it would practically relate its character to the possibilities of bulky moments or of alien elements — then it would have failed precisely, then that would be a painting that is somehow pepped up. >Pimp up my painting. <”

Albert Oehlen in conversation with Alexander Klar, quoted and translated from Albert Oehlen. Fingermalerei, Hagen, Emil Schumacher Museum, 2010, p.34-61; here p.43

In the case of Thomas Arnolds, nameable elements are not controlled by the act of painting, but they get rid of any shackles of identity by the act of “becoming-painting”. In order to illustrate this potential, the paintings have to detour almost any alleged figural representations. The strategic direction is different than Oehlen’s, but the motivation — to produce painting about painting — is similar. He, too, is not content with postmodern reference games, and he is also not oscillating between modernism and postmodernism in that melancholy semi-ironic way (as formulated by the recently emerged theory of “metamodernity”). Here, the project of modernism is being developed further — not in the sense of Greenberg’s teleology, overarching the field from Manet to Reinhardt, but in terms of the expansion and overexpansion of this project’s inherent limits. Painting in the Age of its own durability.

In the series of the less monumental Kitchen paintings (115 by 90 cm) some already familiar utensils are reappearing, but this time as variables of reduced motives and as the result of a second order contextualization. After all, unlike the large-scale paintings, there is nothing stage-like about these works. Along vertical and horizontal axes, the repetitively arranged “objects” take part in the rhythm of what is depicted in a now even more obvious way. In this context, the squares in the painting play a crucial role. They are uniformly lined up on top of each other and being formed from fifteen-centimeter long, fine color bars. In combination with the vertical, prominent and delicate lines (that appear within further, squarely recessed areas in these fields), but especially in conjunction with the schematic kitchen utensils, the close association with slabs or tiles is evident — highly stylized “tiles”, however. What was already suspected becomes apparent in Fliesen A (Klein) from 2008: the fact that these uniform, detailed divergent patterns are not necessarily dependent on the presentation, e.g. of kitchen utensils, in order to fulfill their real task of structuring monochrome surfaces. The same can be claimed for those ornamental elements that stem from a similar haptic characteristic style and which are to some extent already familiar from the large-scale paintings. They are just as little dependent on the linkage with the “objects”. Primarily, they are parts of a pool of figurative-stylized forms that Arnolds has created over the past five years. This repertoire has been carefully and gradually modified. This is why the different elements were not exclusively used in only one series, and not only in paintings.

Apart from Fliesen, Spazieren (International), Klein 1 is the first image that gets along entirely without this pool. The painting was first shown in 2009 in the same-titled solo exhibition at Aschenbach and Hofland in Amsterdam. In Bonn, the just 45 by 75 cm sized piece was hanging between all the red-yellow-blue large scaled works, but was not at risk to be overrun by them. We are, more or less, not talking about something like an apprentice piece or a curious give-away, but about a kind of key to understand the work — precisely because here, the square, grid-like modules are self-sufficient. As long as no further objects can be registered, the lure to interpret the rhythmic system of order as a sequence of tiles or slabs disappears. The dimensions of the painting also allow all of the fine-textured squares to be fully realized for the first time. This is another indication that the modular principle of order in itself does not subordinate the offered area, but becomes visible within a fragmentary section of a potentially infinite pattern — similar to the regular rows of stripes in Frank Stella’s Black Paintings of the late 1950s. The painting is equally primed in red, yellow and blue. The fifteen squares, including the grid-like forms, however, have been applied in white, so that the primary colors, except for two horizontal recessed and linear surfaces, shine through in all places. Here, two alleged final chords of modernity penetrate each other and drown each other out. Already in 1921, the non-figurative reduction to red, yellow and blue was the equivalent to the end of painting for Alexander Rodchenko (Pure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure Blue color). It was exactly thirty years later when Robert Rauschenberg demystified the idealized hermetic of images with his monochrome White Paintings, replacing it with the spatial and situational contingency of the ever-changing white surface. Modernist purity requirements are now of little value as design or action principles — even as an object of denigration. The antagonistic “painting-against” gives way to a decidedly relaxed (not enraptured), at first glance confidently swanky “keep on painting”. The real freedom of this approach is especially justified in the negation of an absolute claim. These models are being carried (back) into the state of appealing painting options by their mutual penetration. No less, but, more importantly, no more.

Mary Heilmann’s Black Sliding Square (Veil) from 1979 is an early example of an antagonistic strategy. The black, square area to the left of the pictorial center can hardly be given the nod as the result of a purely compositional decision. Too powerful is the shadow that is cast by Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square from 1915. Too present are Ad Reinhardt’s Black Paintings from the early 1950s. In this case, the square is completely surrounded by pink color fields and — as if the extravagant surroundings would not be enough — covered almost halfway in pink. As in Spazieren (International), Klein 1, the monochrome surface is visible through the overpainting, and yet the principle of recontextualization is different. Heilmann’s exhibition of the group of pink-and-black paintings in the same year was named Save the Last Dance for Me — after the 1958’s hit by The Drifters. High Art was now confronted with (the knowledge of) Pop and the usually male colleagues had to worry about the dramatic appeal of their claims to autonomy. Engendering Modernism was, is and remains the key word and the mission.

“She uses a delicacy of means to alienate the modernist programme and thereby analyses it at the same time – a tactic that makes her one of the most explicit representatives of new, postmodern painting. A small gesture, a visible brushstroke or some drops of paint in places where our normal historically distinctive perception would not permit it, create a great distance to modernism. Such alterations seem to let the air escape from an overblown, self-assured attitude. Geometric figures lose their weight and use their newly discovered lightness to become affectionate memories of a modernism already passed into history.”

Martin Prinzhorn, Images as the Symptoms of Painting: The Antitotalitarianism of Mary Heilmann, quoted from Afterall, No.5, 2002, p.48-57; here p.50

In his new series °, Thomas Arnolds used only the very color that Heilmann confronted the black surfaces with. Seven monochrome paintings of different sizes in hot pink and pink, respectively. This is the very color that during the late 19th and early 20th Century had a high priority in classic modernism—Picasso’s pre-Cubist pink period in the mid 1900s being a prime example. The situation has changed in the course of the neo-avant-garde of the 1950s and ’60s, when — in Color Field Painting and in monochrome painting — color itself became the carrier of meaning. It seems that the color pink was incompatible with the pathos-laden self-understanding of the Abstract Expressionists in such a manner that Newman’s question in a different circumstance actually should have read, “Who’s Afraid of Pink?”. The differences in color and motifs are considerable, and yet there are some connecting links with Arnolds’ Kitchen and Spazieren paintings of the past three years. This does not only include constitutive stylistic characteristics such as the rigorous insistence on two-dimensionality and a haptic characteristic style. Two works really function as a hinge here: °(4) measures 115 by 80 cm, just as Fliesen A (Klein), and also adopts its internal structure: the division in overall ninety-six compartments (15 by 15 cm each), cropped by the top and bottom edge of the painting. In fact, at least, because the individual structural units are now by definition no longer identifiable as squares.

It is mainly their horizontal edges that survived the transfer to the new group of works — but not without damage. They may not exceed the length of two ex-squares in perfect condition. The resulting gaps are partly considerable, and the line itself is continually being affected by the consequential unrest. At one point it is a U-shaped sag, at another, it branches off diagonally upwards, and elsewhere it sinks downward, convex or concave. Curved, mostly diagonal lines advance into the cleared areas within this scattered grid structure. However, they are no evidence of the fact that spontaneity and speed — indicators of an expressive, intuitive way of working —entered the paintings’ production. They, too, arise from considerately superimposed layers of paint and are significantly protruding from the canvas. Similarities in the course and in the manner of the curvatures give reason to suspect that even the curved lines depend on schematic specifications. The hemispherical paint accumulations, too, partly follow (imaginatively) curved lines — in two places, several of the hemispheres fused completely into a paint bead. The “tiles”, as it turned out, are not representing actually existing entities. They are nothing more than what they are in a material way: combinations of grid-like structures and squares. And even the latter ones are no subjects of an identity-principle, as the juxtaposition of these two works makes clear. They are not irreducible signifiers or smallest order units for the measurement of pictorial surfaces, but simply options of line arrangement.

“Richter, in turn, leaned on Palermo. A few months later in 1969, at a point when the two had grown even closer, Richter titled a small gray painting Blinki, because, as Richter explains, Palermo immediately ‘understood’ the painting when it was just finished. “Certainly I also wanted to honor him with that.” Part of a series of small gray monochromes, the painting seems odd: its grid recedes sharply into the upper right corner to create an illusionistic opening within an opaque plane; modernist monochrome meets traditional perspective. That convergence of outmoded and modern painting devices anticipates the very issues that Richter’s future collaborations with Palermo would confirm. (...) Palermo understood Blinki, because both of them had the same “sense” for quality and the same sense for a crisis, which resulted from the fact that both had dedicated themselves to painting, despite its limited social and artistic relevance at that time.”

Christine Mehring, Light Bulbs and Monochromes: The Elective Affinities of Richter and Palermo, quoted from Lynne Cooke, Karen J. Kelly, Barbara Schröder, Blinky Palermo.

To the People of New York City, Dia Art Foundation, 2009, p.45-78; here p.49-50

When Gerhard Richter and Blinky Palermo started their collaborations in the late 1960s to revitalize painting in a conceptually cleansed manner, painting itself was in a tight spot — not only in Germany.

Pop Art, Fluxus, Performance, Minimal and Conceptual Art subjected any legitimation to a considerable amount of pressure. More than forty years later, not much of that was (and still is) being experienced — a fact that was most unlikely back then. When Arnolds made his paintings of the late 00s years, a decade came to an end that, on reflection, especially baffled us with a disturbingly anachronistic presence of paintings. That is to say, an over-presence and over-production that supplied the art fairs with white noise. This occurred with the beginning of the financial crisis in the fall of 2008 (at latest). As a result, so-called “Flachware” (a German pejorative term that translates literally as “flat commodity”) in convenient formats came to new glory. At the time, painting was being declared dead, and now it is being produced to death. In Arnolds’ °(4), you won’t find the “illusionist opening” of the curved, unraveling grid on the very handy (30 by 40 cm) Blinki. Within the disarray in the grid-like structure, spatiality only emerges in the literal sense—namely, when two of the prominent lines cross. Richter applied the lines onto a flickering color field that had been painted with gestural, relatively thick brush strokes. Whereas in the °-paintings, the lines no longer stand for an aforementioned “modern painting”. They do not dominate any diffuse “blurry” surfaces, i.e. closed systems or independent, unambiguous statements of painting. On the contrary, the static, consistently understated monochrome paint application in °(4) stresses the texture of the canvas and the painting’s object-like quality. In other works of the °-series, the color bars are forming strict boundaries between areas that differ in characteristic style.

More of the curved and slightly curved lines recur in the central area of the right half of °(3) — now forming outlines. A fragile “scaffold” — consisting of several stacked board-like, semicircular to L-shaped structures — projects its two lower ends in a diagonally placed rectangle with rounded corners. In combination with the adjoining trapezoidal fields and a wheel with a corresponding frame, the rectangle proves to be a stylized wheelbarrow tub. This in turn is being carried by an upright male figure that is larger-than-life (the image measures 250 by 200 cm). The direct comparison of these two paintings excellently illustrates Arnolds’ concern of leaving behind the antagonism between representational and abstract painting and of declaring an even more fundamental issue his pictorial agenda: the relation between line and surface. Within this reclusive basic research, the differences between representations that can be associated with abstract painting and those that resemble figurative structures are of a gradual, non-categorical kind. In exaggerated terms, the bodily forms in °(3) are basically nothing more than extremely stretched and curved grid-like structures, while the deranged grid in °(4) results from the highly fragmented and regulated outlines of figurative elements. Two diagonally oriented paint beads are located in the central region of the left half of the painting. They have been applied to exposed areas, such as the top of the left trouser leg and the right front of the jacket — however, without offering representational functions, for example as accessory or appliqué. This evidence of a particular relief-like approach to painting (one is almost tempted to speak about “pure painting”) literally wrecks the figure’s representative potential. Moreover, it serves the image’s structure — along with three circular paint accumulations and a system of five horizontal and vertical stripes, which extends almost over the entire surface. One of the two vertical thin stripes, coming from the top of the screen, meets a much wider one. The second line connects the first one with the upper corner of the wheelbarrow tub and marks the vertical center — just like the edge of the door in Küche 2 or the edge of the cabinet in Spazieren (International) Groß 1. From this corner, a thin stripe extends to the right edge of the painting, while the second broad stripe runs at ankle height. With their lateral grooves and shapes, both stripes are identifiable as schematic profiles of tongue and groove boards (Fig. 13). This designation emphasizes their function as a classification system that is intrinsic to painting. The interlocking of apparently primary structural elements with the allegedly figural components finally causes the inability to locate the latter in any (even the most diffuse) representational pictorial space. Within this unusual arrangement, the lines operate like membranes; they are as much a part of the defined areas as the more loosely painted fields “in between”.

“It is the confrontation of the Figure and the field, their solitary wrestling in a shallow depth, that rips the painting away from all narrative but also from all symbolization. When narrative or symbolic, figuration obtains only the bogus violence of the represented or the signified; it expresses nothing of the violence of sensation – in other words, of the act of painting.”

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, London, 2005 (orig. 1981), p.xiv-xv

In some cases in °(1) (image on page 19), the individual elements of this arrangement reappear in a drastically reduced and modified form. As already in °(3), a schematic, almost clumsy representation of a middle-aged person can be seen: bespectacled again, this time shaven and wearing a hat. All of the °-paintings are executed in “skin-color”, the shade’s official name. Yet the choice of color does not allow any hasty conclusions on the paintings’ real subject, because, in contrast to Francis Bacon’s portraits, it is not about the appearance of skin or flesh. Not physicality is the object of obsession, but the artificiality of the make-up. Unlike in °(3), only a few areas are being thickly executed here. The canvas is mainly covered by a subtle application of color. The canvas is simultaneously being covered and accentuated and thus becomes more than just a work surface. A segment of the covered canvas, which is circumscribed by lines, is corresponding to a face that is covered with skin-colored paint, and vice versa. The fact that the latter is a self-portrait can only be identified at second or third glance. However, the sum of characteristic details— the hairline, for example, or the distinctive glasses — provide a measure of similarity that finally allows this conclusion. The reason for the even more abundant un-virtuose implementation (which leads to a rather unflattering representation) is a conceptual one. Thus all the curved lines were executed with the aid of commercially available curve templates, as it was already the case in °(3) and °(4).

What looks like the fragments of a neck brace, are in fact modified miniature versions of the curved shapes from °(3). Just as in that situation, they determine the right half of the painting in °(5) and form a psychedelic symbiosis with the centrally placed figure that appears to reach out a hand to the viewer in °(2). In °(7), the shapes even take over the command of the entire painting, while at the same time, figures are only indicated in a shadowy manner and as abstracted body fragments. The curved shapes are without doubt the central motif and, thanks to the artist’s hint, are identifiable as sauna benches. They represent a place of a ritual act, defined by the combination of different aggregate states — hence the exhibition title. Within Arnolds’ classification, ice, water and the act of pouring water on the hot stones represent point, line and surface. The sauna benches are, even more than the self-portraits, no longer just occasions for painting. And yet, the whole thing is still a solipsistic, even cryptic matter. The fact that the self-portraits are not performing a narrative or even representative function is particularly being symbolized in °(1). Contrary to the conventions of representation, the outlines of this decontextualized head are not located in the top half of the painting. They are slipped in such a way that the lower rims of the glasses run at the level with the central axis.

“Bacon often explains that it is to avoid the figurative, illustrative, and narrative character the Figure would necessarily have if it were not isolated. Painting has neither a model to represent nor a story to narrate. It thus has two possible ways of escaping the figurative: toward pure form, through abstraction; or toward the purely figural, through extraction or isolation. If the painter keeps to the Figure, if he or she opts for the second path, it will be to oppose the “figural” to the figurative. Isolating the Figure will be the primary requirement. (…) Isolation is thus the simplest means, necessary though not sufficient, to break with representation, to disrupt narration, to escape illustration, to liberate the Figure: to stick to the fact.”

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, London, 2005 (orig. 1981), p.2

Once more, now in the upper left corner, three circular paint accumulations appear in the large scale painting °(5), which is sized 250 by 400 cm, just like the Kitchen paintings and °(6). The nearly hemispherical, plate-sized and finely-executed accumulations — most likely the most relief-like way of painting ever — are also the central motif of °(7) (Fig. 14). Just like its counterpart Spazieren (international) Klein 1, the only 45 by 75 cm large painting can claim to be a veritable bundle of energy within a series of large-scale works. The lower left half of °(5) is dominated by the representation of an automobile in profile. The painting’s left edge crops the auto body at just behind the front passenger door, while the front third of the car hood extends across the painting’s middle, together with the Star that directly identifies this pictorial element. In the car sits the now familiar, casually dressed person, holding the steering wheel with both hands and turned towards the viewer with a slightly strange expression on his face. Here, at the very latest, the caricature traits of the self-portraits are unmistakable. Particularly those self-portraits indicate that the °-paintings are, despite all their theoretical (and practical) finesse, definitely imbued with an anarchic humor. This kind of humor ignores the so-called unwritten laws — conservatism’s greatest evil — and opens the door to presumed inconsistencies. Especially within the transfer to such a highly reputable terrain as monochrome painting, Surrealist combinatorics shows its continuing effectiveness. Lautreamont combined a sewing machine with an umbrella; in Arnolds’ case it is a sauna bench and a Mercedes-Benz (Fig. 15). The monochrome canvas becomes a dissecting table. Placeholders for portrait and genre painting collide, and barely identifiable and decodable elements come together on equal terms. And the distrust towards narrative, metaphoric or representative contexts of meaning is noticeable. The result of this continued infiltration processes is a form of egalitarian, libertarian, in a Deleuzian sense figurative painting.

“The whole thing is getting away from painting at the same time I’m painting. I am making a Still Life, but the activity of making a Still Life is so silly to me that I don’t want to be making a Still Life. This is a way of removing myself from the stupidity of doing that sort of thing so it becomes a non-painting, at the same time it is a painting. I don’t think of that while I’m doing it but I guess it’s behind it. I mean, what can you really paint that isn’t ridiculous.”

Roy Lichtenstein, video interview with Hermine Freed, 1972, quoted from Roy Lichtenstein: Meditations on Art, Skira, 2010, p.193

Translation: Sonja Engelhardt

Biography

1975 born in Geilenkirchen/Germany

1997–1999 Apprenticeship as stonemason and stonesculptor, Aachen

2000–2001 Practice as ecclesiastic conservator, Bistum Diocese Aachen

2001–2005 Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig (class of Walter Dahn)

Lives and works in Cologne

Solo Exhibitions

2018/2019

Duktusinduziert, Leopold-Hoesch-Museum, Dueren/Germany

2018

DOUBLE SUNDAY (red or blue), ak-Raum, Cologne

RUN, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, CologneHIGH

HIGH and SAFE, Kunstverein Heppenheim

2017

LUFTHAUS, ak-Raum, Cologne

2016

MARB7, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Galerie Matthias Jahn, Munich

2014/15

Kunstverein Reutlingen

2013

Peng!, Regina Sprüth, Cologne

Luft #1, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2011

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2010

Papier / Öl / Luft, Gloria, Berlin (catalogue)

Rausspazieren, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2009

Spazieren (International), Aschenbach & Hofland Galleries, Amsterdam

Bobby und Snake: Wonderful Life (with Tim Berresheim), Jagla, Cologne

2007

Klinkerexpressionismus, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Ich mach’ klar Schiff, FYW, Köln Cologne (catalogue)

2006

Lake (with Tim Berresheim), FYW, Cologne

2005

F.Y.W. (with Tim Berresheim), Uberbau, Düsseldorf

Group Exhibitions

2018

Trance, Aïshti Foundation, Beirut/Lebanon

RE-VISION, Kunstmuseum Bonn, Bonn

Geheimnis der Dinge. Malstücke (curated by Hartmut Neumann), Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art, Duesseldorf

2017

PLAN VIEW, Jahn und Jahn, Munich

Back to the shack, Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles

Selvskabt Modvind, Sunday-S Gallery, Copenhagen/Denmark

Thomas Arnolds, André Butzer, Daniel Mendel-Black, Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

Berlin–Klondyke, UGM Studios, Maribor/Slovenija

2016

Der Funke soll in Dir sein –curated by André Butzer, Salon Dahlmann, Berlin

Papier, ak RAUM, Cologne

Schau 3, Kunsthaus Kollitsch, Klagenfurt/Austria

Surface as interface as surface, Carbon 12, Dubai/UAE

2015

DIE 1. BERLIN EDITION von BERLIN-KLONDYKE, Salon Dahlmann, Berlin

2014

17 abstract paintings, Wertheim, Cologne

Wo ist hier? #1: Malerei und Gegenwart, Kunstverein Reutlingen/D

in der Wohnung, Alte Fabrik. Gebert Stiftung für Kultur, Rapperswil/CH

Bien Merci // Stand der Dinge, Wertheim, Cologne

Fürchtet Euch nicht! Bestimmung des Feldes zu einer gegebenen Zeit: Malerei nach 2000, Neue Galerie Gladbeck

2013

A bis W, Q.H.S.O.I.Q.O.C.M.S., Berlin

Berlin–Klondyke, Spinnerei Leipzig sowie as well as Hipphalle Gmunden

2012

There is ... Reflections from a damaged Life?, b-05 Montabaur

Berlin–Klondyke, Neuer Pfaffenhofener Kunstverein

2011

Abstraktion. Sammlung Oehmen / Sammlung Bergmeier, Kunstsaele Berlin

Dormition, Galerija Contra, Koper

Diktatur Charlottenburg, Kosmetiksalon Babette, Berlin

Berlin–Klondyke, Klondike Institute of Art & Culture, Dawson City

Papierarbeiten, Jagla, Cologne

2010

Der Westen leuchtet, Kunstmuseum Bonn

La Grande Dimension, Walzwerk, Düsseldorf

Crefelder Gesellschaft für Venezianische Malerei, Galerie Börgmann, Krefeld

2009

De Nieuwste Collectie, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

FYW 573 km, Montgomery, Berlin

Up & down (WTF). Neue Arbeiten, FYW, Cologne

2008

My Generation, Patrick Painter Inc. / Peres Projects / Reiner Opoku, Cologne

Regarding Düsseldorf, 701, Düsseldorf

2007

bye, bye Acapulco, Acapulco, Düsseldorf

Institut für zeitgenössische Beobachtung, Vienna

Tonskulpturen, FYW, Köln Cologne

Publications

2014

Edited by Christian Malycha

german/english

With a conversation between TA and

Heide Häusler and an essay by CM

30 x 24 cm, 64 pages

Holzwarth Publications, Berlin

Exhibition catalogue Kunstverein Reutlingen

2011

Essay by Wolfgang Brauneis

german/english

21 x 28 cm; 31 pages

Exhibition catalogue Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2007

Essay by Wolfgang Brauneis

21 x 15 cm; 46 pages

Exhibition catalogue Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne

2010

Group exhibition, accompanying catalogue

Ed. Stephan Berg, Stefan Gronert

german/english

29,2 x 22,8 cm; 416 pages

Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld

Exhibition catalogue Kunstmuseum Bonn

2007

Essay by Jonathan Meese

29,7 x 21 cm; 25 pages

Exhibition catalogue UBERBAU, Düsseldorf

2010

Essay by Christian Malycha

29,7 x 21 cm; 12 pages

Edited by Christian Malycha

Exhibition catalogue Gloria, Berlin

2010

Exhibitions secretary: Christian Malycha

German

29,7 x 21 cm, 32 pages

Exhibition catalogue Galerie Börgmann, Krefeld

2007

21 x 15 cm; 16 pages

Exhibition catalogue FYW, Cologne

2012

Edited by Christian Malycha

german/english

With contributions by Theodor W. Adorno,

Bruno Hillebrand, Albrecht Hornbach,

Robert Kudielka, Hendrik Lakeberg,

Volker Pietsch, Klaus Theweleit, Andi Schoon

24 x 17 cm, 176 pages

Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld

Exhibition catalogue b-05 Montabaur

2014

29,7 x 21 cm, 16 pages

edition: 1–200 / 200

Frank’s Grapefruit

Grafton / Massachusetts, 2014